A personal history written and submitted by Jim Anez, Miles City Flight Service Station

I started with the FAA at the Miles City Flight Service Station (FSS) on June 30, 1975. The facility was starting a staff rebuilding phase and one new hire was at the Academy in Oklahoma City when I arrived. In July we got another guy, and then another in August and two more in September. My first month and a half were spent at the facility doing whatever the specialists and manager could teach us to do. We got pretty good at transmitting flight plans on the teletype but we had no idea what we were doing. We only knew the format to be followed and if it was wrong we’d get an error message, get teased, and have to do it again. Two of us went to the Academy in September; the guy who started in August went in October and so on. As soon as a new guy became productive one of the “old timers” would transfer. A year later, by the summer of 1976, the entire staff (except for one guy and the facility manager) had started in 1975. By the summer of 1977, due to more transfers, there were only four specialists, all of us having started in 1975. That was a hard summer, with few vacations and a lot of overtime, but it was very rewarding because all of us had started at the same time, we had nearly identical training, and we all got along well.

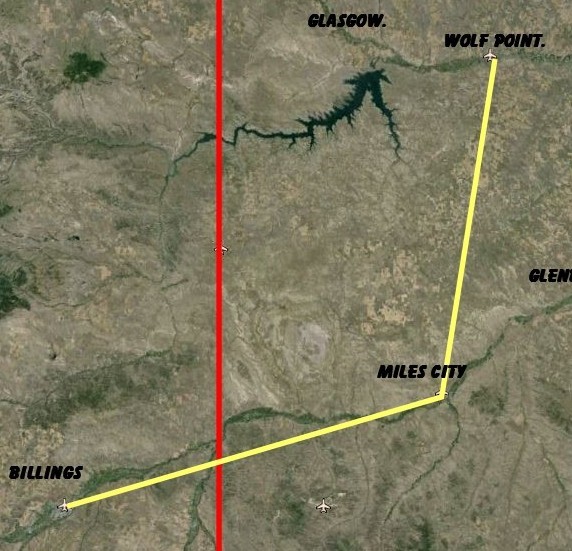

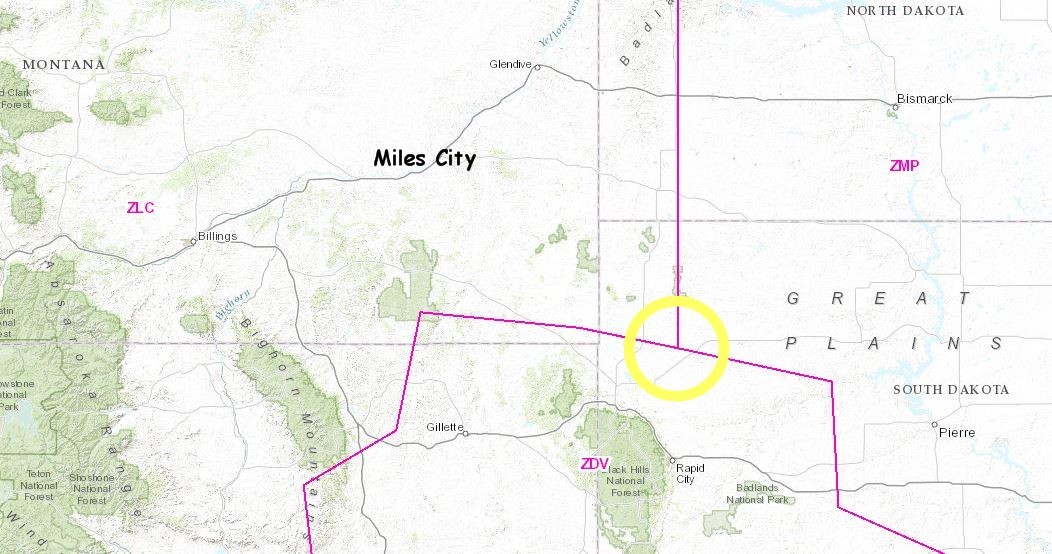

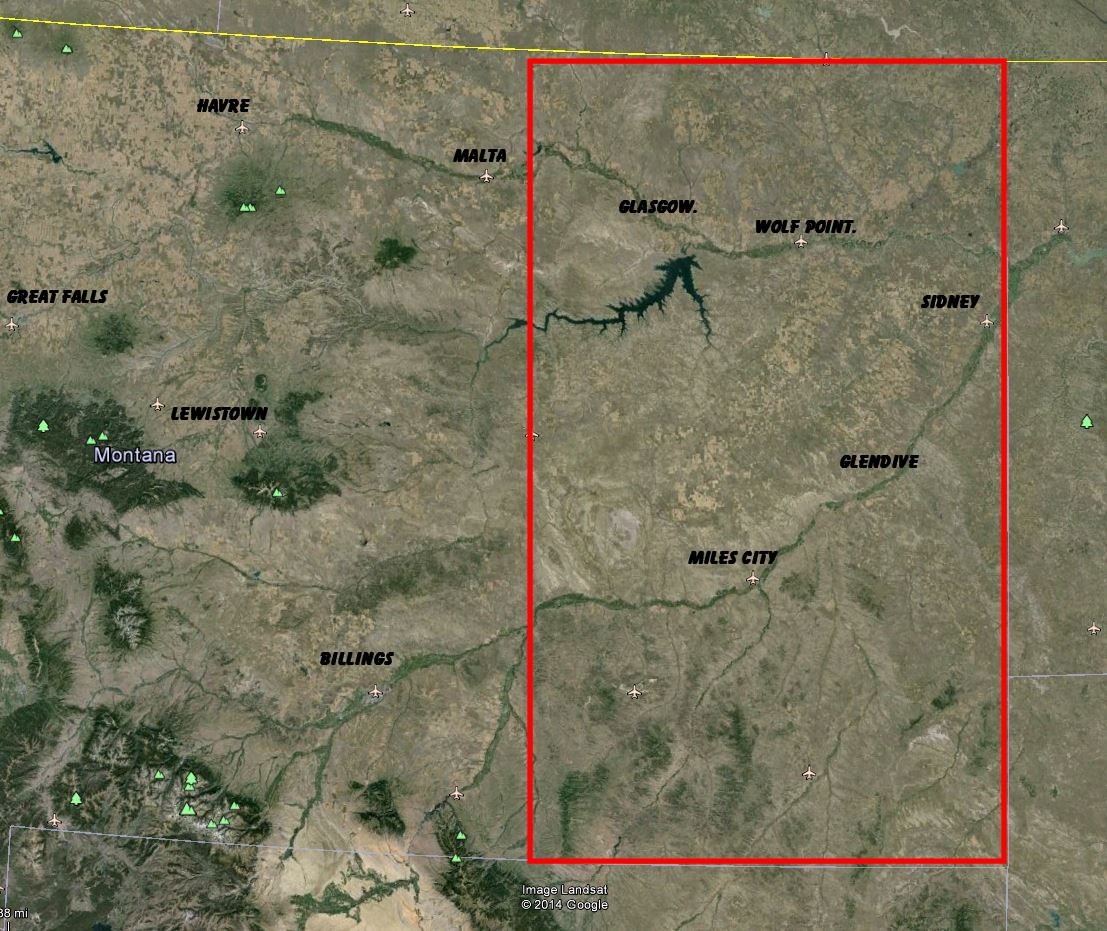

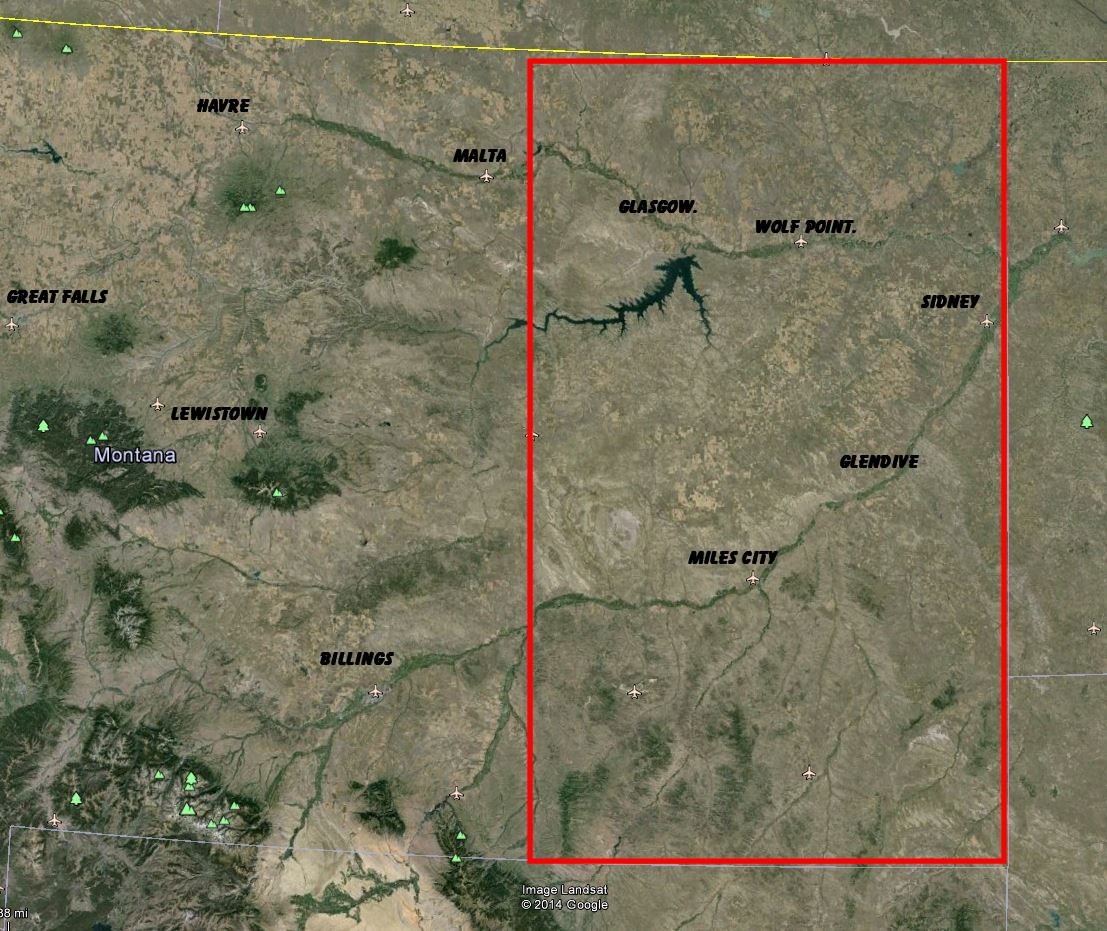

The Miles City FSS flight plan area was approximately the eastern quarter of Montana from the Canadian border to the Wyoming border, about 40,000 square miles. Billings, Lewistown and Great Falls had the flight plan areas to the west, Minot, Dickinson and Rapid City had the flight plan areas to the east and Sheridan had the area to the south in Wyoming.

The Miles City FSS flight plan area was approximately the eastern quarter of Montana from the Canadian border to the Wyoming border, about 40,000 square miles. Billings, Lewistown and Great Falls had the flight plan areas to the west, Minot, Dickinson and Rapid City had the flight plan areas to the east and Sheridan had the area to the south in Wyoming.

I liked Miles City. It was a good place to work and not a bad place to live (at least for a kid from a similar Montana city). Because of our large area of responsibility and distances between airports our work load was almost evenly divided between radio and pilot briefing and it was never dull.

WEATHER ISSUES

Conflicting Needs

When I arrived at Miles City in the summer of 1975 there were two special projects operating from the airport. One crew in a Lear jet was doing high altitude infrared photography and they needed absolutely clear sky. The other operation involved weather modification and the study of developing of thunderstorms. They wanted clouds. The two groups were in the flight service every day checking weather and somebody was always unhappy when they left.

High altitude photography

One day during July the Learjet guys got a clear day and were going to fly. As I mentioned it had to be absolutely clear – even thin cirrus affected the infrared so they waited and watched much more than they flew.

They asked if any of us wanted to go along and, because I was the new guy and not at all productive, I was allowed to go. There was a huge camera mounted on the floor of the cabin and only two seats in the cabin. They flew north-south tracks over the area between the Missouri River and the Yellowstone River in eastern Montana, and had to be at a very precise altitude, as I recall, 40,500 feet. From 40,000 feet eastern Montana in July looked just like the WAC charts that we used.

They flew for about an hour and made 3 round trips during that time. When they finished the south end of the third run the pilot almost literally dove to get down without overshooting Miles City. The aircraft was in such a steep descent it was all I could do to avoid sliding out from under the seatbelt.

At the end of the week I drove back to my home in Havre, MT. Interestingly it took me three hours to drive to Glasgow, the distance the Lear had flown six times in one hour!

Weather Modification

What we called weather modification was really the data gathering and study phase of a program that ultimately hoped to lead to some kind of weather modification program.

The operation involved three aircraft, a B26, a Beech Queen Air and a Piper Navajo.

The aircraft had all kinds of instrumentation and they would simultaneously fly (at different altitudes) into clouds that were developing into thunderstorms to sample conditions. Support personnel on the ground included a meteorologist and a bunch of scientists. They had an early generation Doppler radar system and a large array of rain gauges spread over several thousand square miles in southeast Montana. Data from the aircraft, radar and the precipitation readings from the rain gauges were collected and studied.

The aircraft had all kinds of instrumentation and they would simultaneously fly (at different altitudes) into clouds that were developing into thunderstorms to sample conditions. Support personnel on the ground included a meteorologist and a bunch of scientists. They had an early generation Doppler radar system and a large array of rain gauges spread over several thousand square miles in southeast Montana. Data from the aircraft, radar and the precipitation readings from the rain gauges were collected and studied.

Every day their meteorologist would come into the flight service, study all the charts and weather data, and give his crews a briefing on whether there was likely to be convective development that day. In 1975 he would categorize the likelihood of storms as “yes”, “no” or “maybe” and the flight crews would plan their day accordingly.

During the summer of 1976 the meteorologist no longer had the “maybe” option. He had to say “yes” or “no” and had to predict “when”. It was amazing how close he could come to the precise time that we would begin to see the convective development – usually with 15 minutes of the time he would predict.

One day as storm development began all three flight crews rushed in to file flight plans. They all wanted to depart at the same time and go to the northeast, but Miles City was an “uncontrolled” airport so normally each aircraft had to wait for departure clearance until the controller at Salt Lake Center was talking with the previous departure.

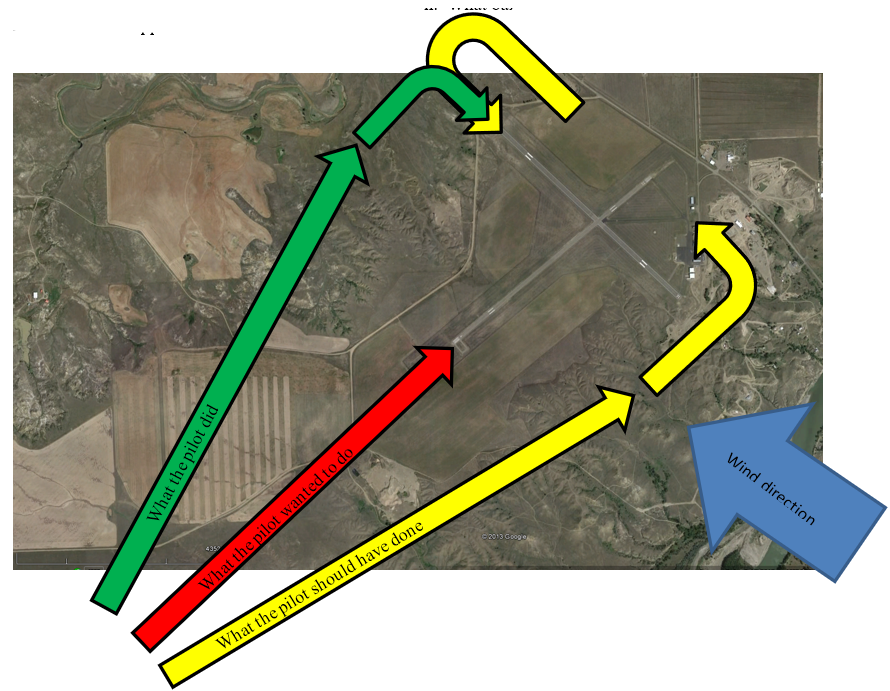

In this case the controller gave me clearances for all 3 at the same time. The B26 was to depart runway 04 and climb on course to the northeast, the Queen Air was to depart runway 12 and turn left on course to the northeast and, finally, the Navajo was to depart runway 22 and fly southwest to cross the VOR heading southwest at or below 5000’ then climb southwest of the VOR so as to cross the VOR northeast bound at or above 9000’. I didn’t know it at the time but the reason for this was that there was traffic crossing the VOR from northwest to southeast at 7000.’

I must have read the clearance to the Navajo five times before the pilot read it back correctly. That was fortunate because by then everyone in the FSS, including the facility manager, was standing next to me listening when the pilot finally read it back correctly.

A while after all of the aircraft had departed I got a call from the controller in Salt Lake City asking me to read back the clearance I’d given the Navajo. I did and it was what he’d given me. He then asked if the pilot had read it back correctly and I assured him that he had and that three other people could verify that (we didn’t have recorders). He then instructed us to have the pilot call Salt Lake City when he got back to the airport.

I learned later that the Navajo had crossed the VOR at 5000’ heading southwest, then turned around and reported over the VOR at 7000’ heading northeast. Within a minute the transient aircraft reported over the VOR at 7000’ heading southeast. Both aircraft were in the clouds and they were on different frequencies so they didn’t know about each other and no one knows how close they might have been to each other. (Radar coverage over that part of Montana began at around 10,000 feet).

I was off duty when the aircraft returned so don’t know exactly what happened but there were new pilots flying the Navajo the following week.

[I have often wondered why the controller didn’t have the Navajo depart runway 30 with an altitude restriction and turn right after departure. But it is what is is.]

Flying the mail in winter

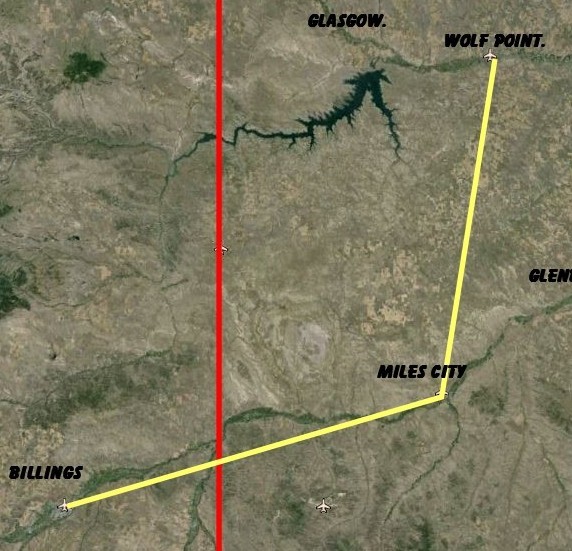

A company based in Denver flew mail from Wolf Point to Billings with a stop in Miles City every night.

A company based in Denver flew mail from Wolf Point to Billings with a stop in Miles City every night.

The pilot, in Wolf Point, would check weather and file flight plans with us early in the evening then arrive about 2200 enroute to Billings. He would return to Wolf Point stopping in Miles City between 0200 and 0300 each morning. The Aero Commander 500 aircraft they flew were used hard and, by most accounts, weren’t in the best of shape.

One cold winter night, with temperatures around -15 and a little wind, I got a call from Salt Lake Center that an Aero Commander 690 had lost an engine and would be landing at Miles City. They did not declare an emergency and landed uneventfully. Shortly after they landed one of the pilots came into the FSS and introduced himself. He was the owner of the company that had the mail contract and asked if I would let his pilot know that they would need a ride to Billings when he stopped with the mail.

Soon after that an older guy came into the FSS. His face was beet red and he was really huffing and puffing from having been out in the cold. It turned out that he was the chief mechanic for the company and had opened the engine covers to try and figure out what had happened to the engine on the AC90.

When the mail pilot called from Wolf Point to check weather and file flight plans, I advised him that he’d have two riders from Miles City to Billings and who they were. His response was that it was good because he was flying a plane with no heater and maybe if they had to fly in it they’d do something about fixing the plane.

I let the owner know that I’d relayed the message and that they should be bundled up because the AC50 didn’t have a heater. His response was to send his mechanic back out to remove the heater core from the disabled AC90, and when the AC50 arrived they installed the heater in it.

The next week when I talked to the pilot of the mail plane, the events of the previous week came up and I commented that at least he got a working heater for his troubles. He said, “Not true, the SOB removed it when they got to Billings, I’m still flying without heat!”

Weather Observation hazards

In addition to assessing sky condition and visibility we had to obtain temperature readings for each weather observation. This involved a trip to the instrument shelter and a 2 to 5 minute stay to allow the “wet bulb” thermometer to be read accurately.

I’d started working shifts alone in November so obviously the weather wasn’t the greatest. One dark evening when the temperature was in the low 30’s and it was raining sideways because of the wind, I stood in the doorway for a moment and the thought crossed my mind that I could fake the temperatures this one time and no one would ever know. Then it occurred to me that less than six months earlier I’d been delivering Coca Cola and often worked in weather like this all day long – I could certainly go outside for five minutes. I never again hesitated to do what had to be done to take accurate weather observations.

There were cautionary tales about the dangers of lightning, etc., and we heard about the guys at Miles City who found rattlesnakes warming themselves on the sidewalk between the building and the instrument shelter. While I was there we never had any snakes but one day the specialist had to report the temperature as “missing,” and in remarks he had recorded “skunk under instrument shelter.”

One night, as I was leaning into the shelter to read the temperatures, I heard someone behind me and then someone put a hand on my shoulders. I spun around to find the biggest, friendliest Chocolate Lab you’d ever care to meet staring at me with that “watch doing” look in his eyes.

Gut Feeling (Sometimes things just happen the way they’re supposed to)

Miles City was an airport where a lot of general aviation pilots stopped for fuel and weather briefings so we had a fairly regular stream of walk in weather briefings. This particular day the weather in eastern Montana was broken to overcast ceilings between 4000 and 6000 feet and very strong winds with a lot of turbulence being reported.

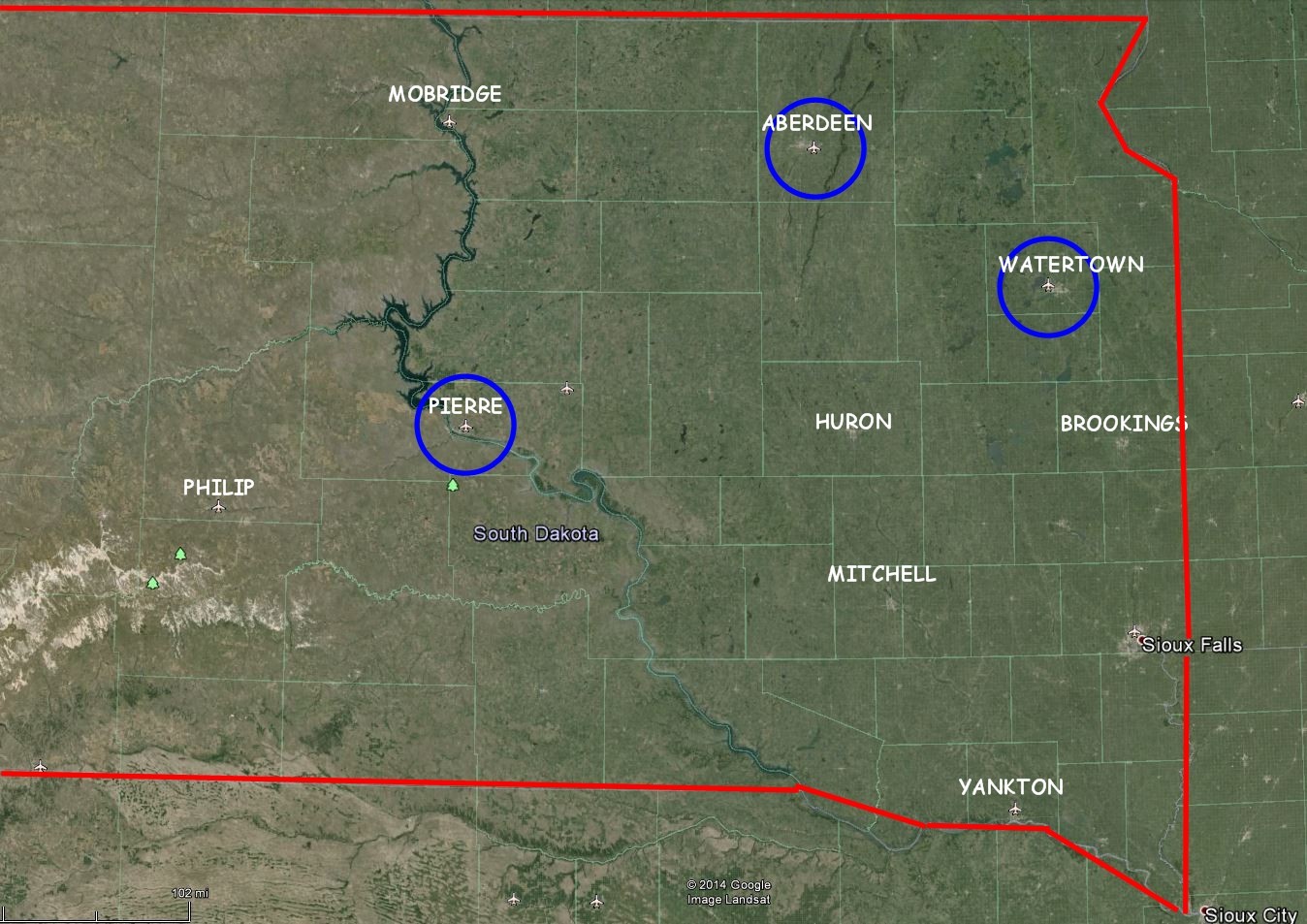

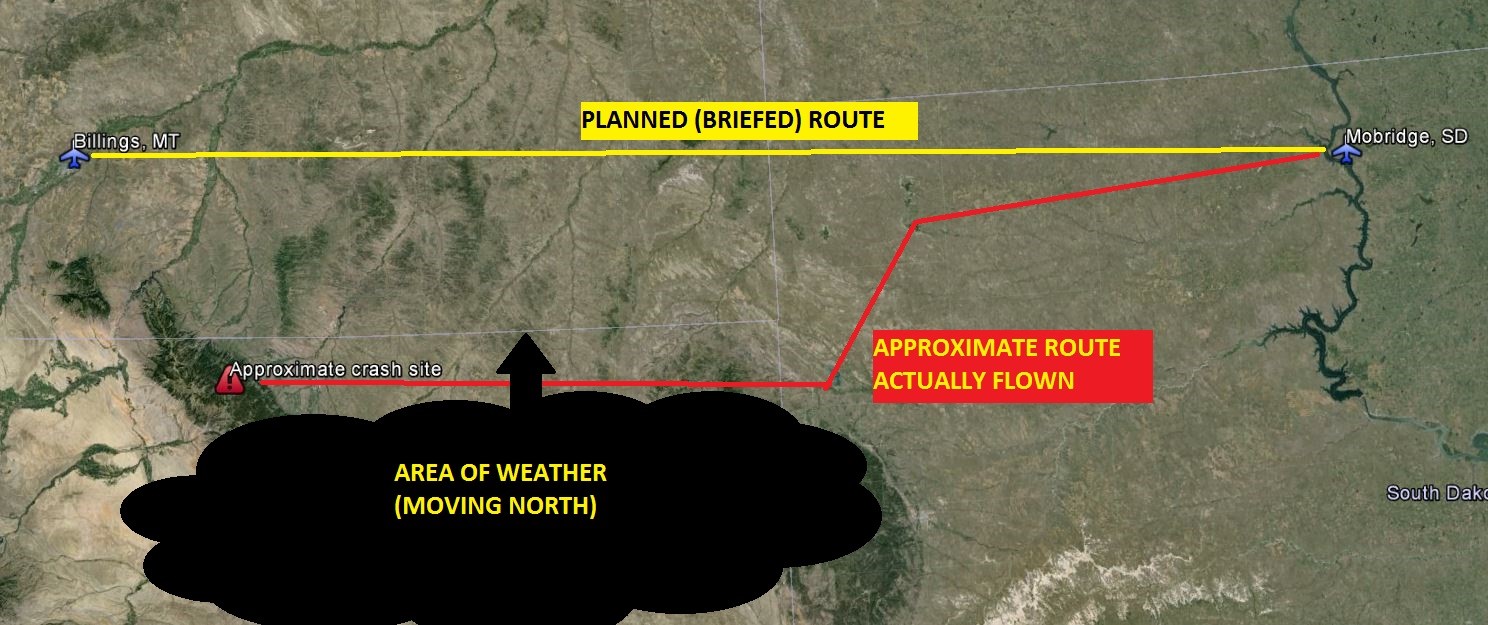

I had just talked with a Canadian pilot flying a Piper Comanche heading southeast to central South Dakota. I’d advised him to expect ceilings to drop to around 3000 feet in northwest South Dakota and that those conditions should prevail all the way to his next stop. The guy seemed very competent and I didn’t think that those conditions should be any problem for him.

A short time later another pilot came in. He was with his wife and 2 daughters and they were in a Cessna 182 heading essentially the same direction. This guy seemed uncertain and somewhat concerned about the conditions.  The more I talked with him the more I tried to discourage him continuing that afternoon. He’d talk with his wife a bit then we’d look at additional reports and then they’d talk some more. He made a couple of phone calls and eventually asked about getting a cab – he said they’d decided to take a bus to Billings and get a commercial flight to where he was heading.

The more I talked with him the more I tried to discourage him continuing that afternoon. He’d talk with his wife a bit then we’d look at additional reports and then they’d talk some more. He made a couple of phone calls and eventually asked about getting a cab – he said they’d decided to take a bus to Billings and get a commercial flight to where he was heading.

I told him that I was getting off duty soon and I could give them a ride if they wanted to wait. He was fine with that and I gave them a ride into town when I got off work.

On the way into town I learned that he was from Missoula. He asked if I knew any of the guys in Missoula and I mentioned that I was acquainted with a guy who worked in the Tower. He asked if I liked Flight Service and I said I did because I really felt like we helped pilots and enjoyed the personal contact. I said something like, “We don’t often get into life and death situations but I feel like it’s a really valuable service.” His response was that I should consider that I saved the life of 4 people that day because he was convinced that if he’d continue his flight they wouldn’t have made it. He said the turbulence had been so bad from the Rockies east that he was beat, and if he’d continued into the marginal conditions I’d described, the consequences wouldn’t have been good.

Visibility too good?

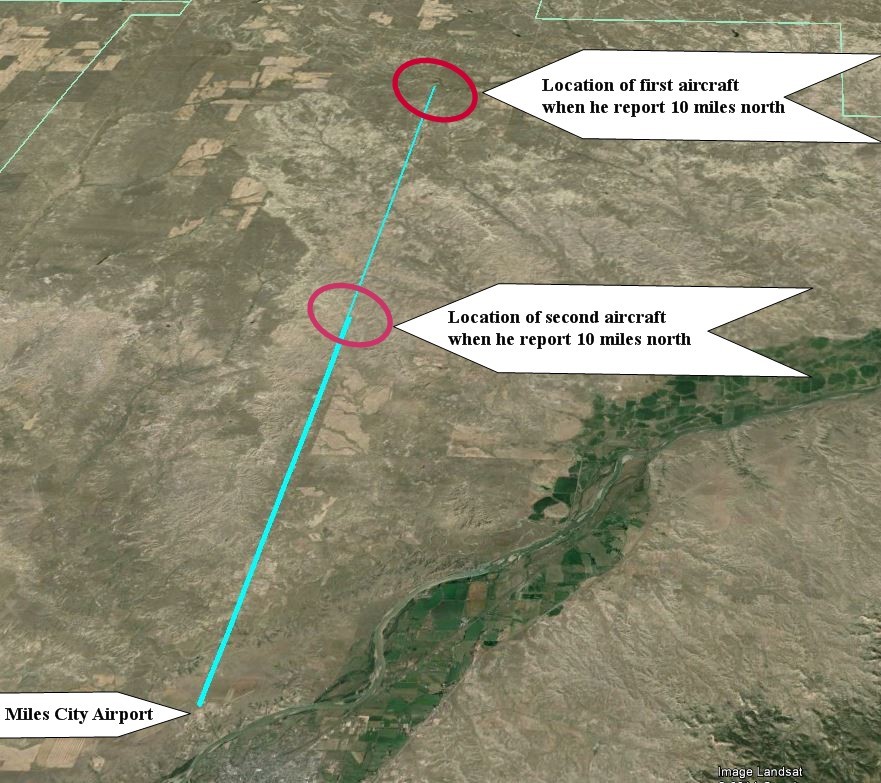

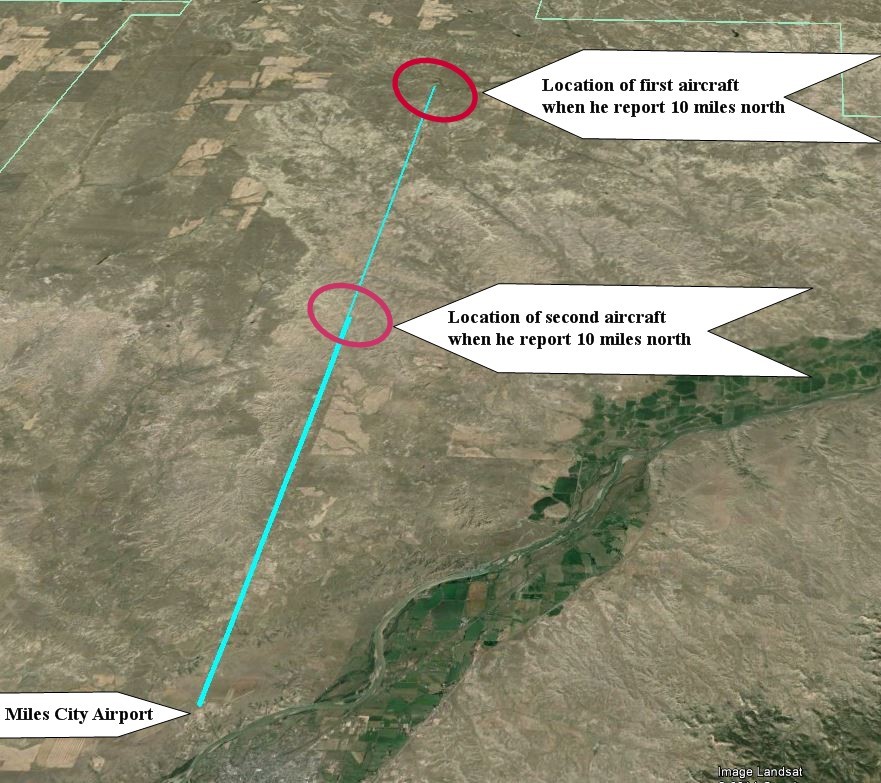

I was on the radio one day when an aircraft called for an Airport Advisory stating that he was 10 north of the airport. Out of habit I glanced at the DF and it indicated a bearing of about 360º. Moments later I received a call from another aircraft, who also said he was 10 north and inbound to land; and again the DF showed about 360º. I gave the advisory and traffic and alerted both planes that I was showing them both on the same bearing. They both responded that they were looking, but neither saw the other.

A bit later the second aircraft landed with still no sign of the first aircraft. I called him and he reported that he thought he was about 10 north (still?).

Later when the first aircraft finally landed the pilot came into the FSS. He apologized for the confusion and explained that he was from Ohio and back there when you could see something you had to be within about 10 miles. He said he must have been 20+ miles out when he saw the Yellowstone River and just wasn’t used to it being so clear that you could see things that far away.

The Wild West

I had the opportunity one day to visit a ranch somewhere out in the Powder River basin southeast of Miles City. I don’t really know where it was – I just know it was a long way from anywhere. As we drove up to the ranch house I noted that there was a Piper Cub and a Cessna 182 parked near one of the out buildings so I thought I’d have something in common with the rancher.

The rancher asked me what I did a couple of times and it became obvious that he didn’t know what a Flight Service Station was. I told him that when he flew into Miles City I was one of the guys he talked to on the radio, and his response to that was even more of a surprise to me. He said he didn’t like using the radio and he’d never think of flying into a big airport like Miles City! He just used his planes to keep tabs on his cattle.

I wondered at the time how many other ranchers had aircraft that we knew nothing about and likely weren’t even properly registered. Several months later I had my question partially answered.

The Air Force Rescue Coordination Center was just started to use satellites to detect and locate transmission from Emergency Locating Transmitters (ELTs) in those days. ELTs are designed to automatically trigger when an aircraft is involved in an accident but in my experience, probably 90 percent of the signals were inadvertently triggered by hard landings or other non-emergencies. When the Air Force got an ELT signal they would calculate a rough location and they would contact the nearest FSS. We would then contact airports near the location and attempt to try to eliminate the possibility that the signal was inadvertently triggered from an aircraft on the airport.

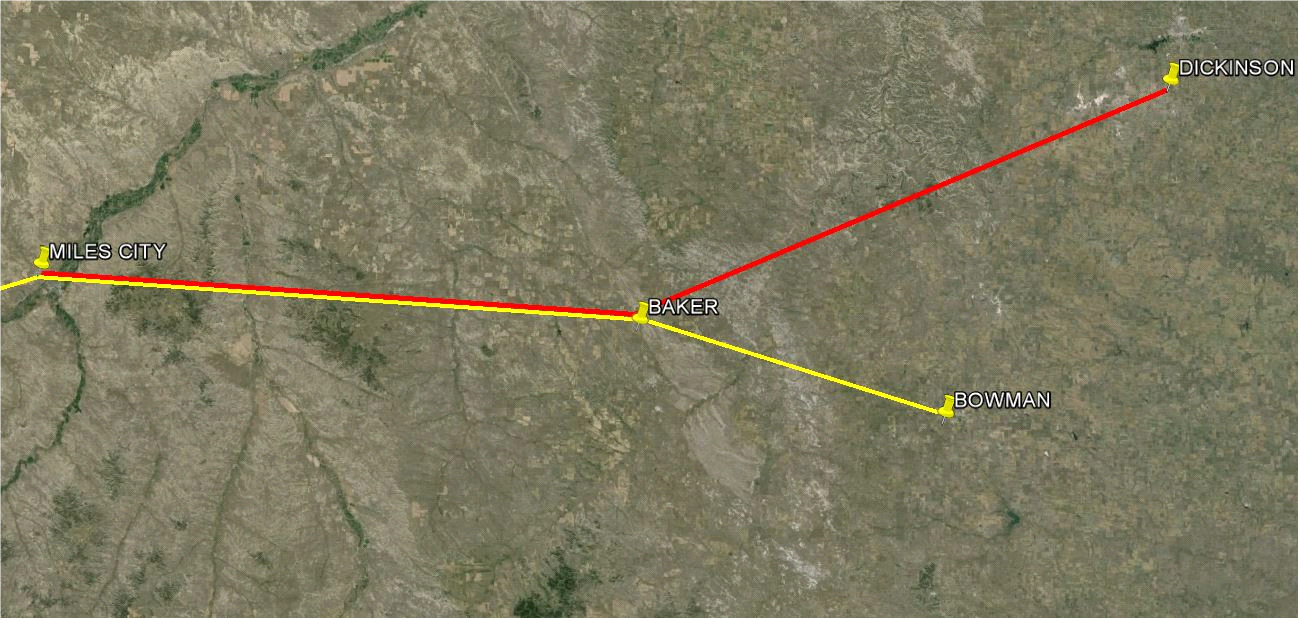

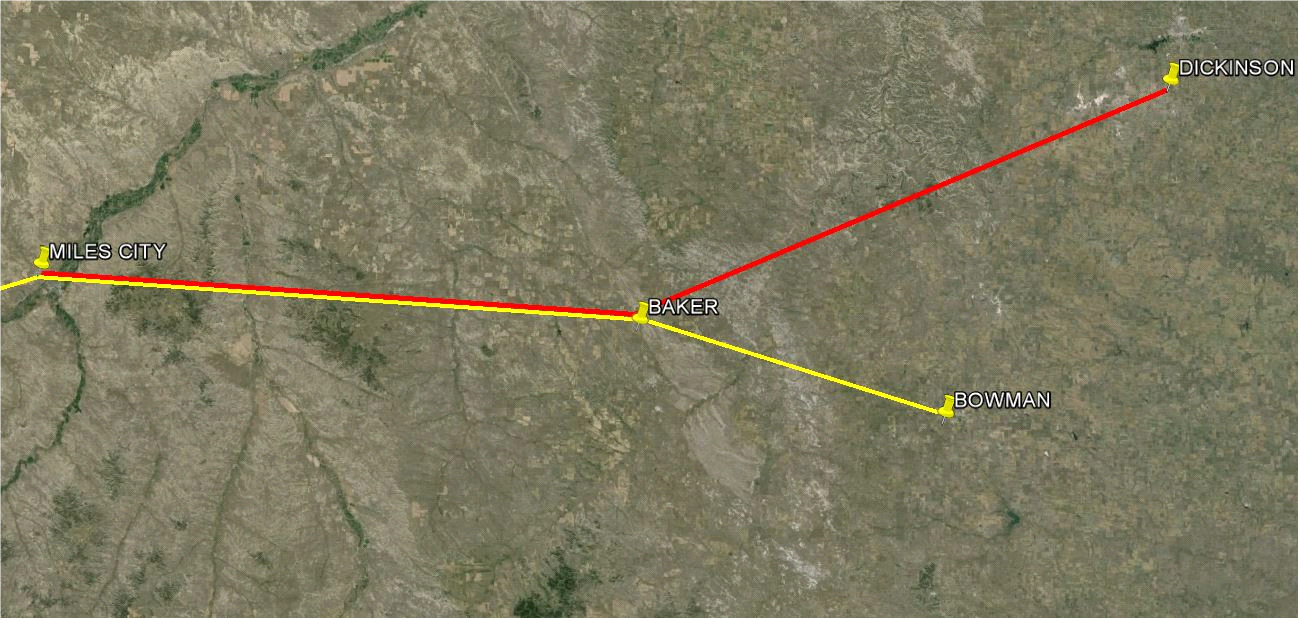

On one day, after my ranch visit, I got a call from the Air Force RCC saying they were receiving an ELT from the vicinity of Baker, MT (about 80 miles east of Miles City). I contacted the Baker Airport and they advised the signal wasn’t from an aircraft on their field, and in fact, they couldn’t hear any ELT signal on the ground.

We always figured the satellite locations were somewhat inaccurate, but there were no other airports anywhere near Baker so we were stumped. Recalling my experience with the rancher and the suspicion that there were aircraft on ranches that we knew nothing about, I called one of the local pilots in Miles City who sold insurance and seemed to know every rancher in southeast Montana. I asked him how many aircraft he thought might be on ranches east and south of Miles City that weren’t “on the books”. His estimate was there might be as many as 50 but he said not to worry because if they ever had ELTs installed they would have been removed or the batteries were dead.

Dickinson FSS finally located the aircraft with the active ELT. It was coming from an aircraft that was in a steel Quonset building on a ranch near Bowman, North Dakota (about 40 miles east of Baker). The officer at the Air Force RCC speculated that the shape of the building focused the signal towards the west causing the satellite to “locate” it in the Baker area.

If It Ain’t Broke

There was a spray pilot who lived in a small community about 60 miles northwest of Miles City. He had a strip at his farm place but would sometimes fly out of Miles City, and during the summer we talked with him several times every day. One morning when I went to work at 8am I was advised that I should expect someone from State Fish and Game to come out during the morning to pick up a dead dear that was on the side of the runway. It seems the spray pilot hit the deer while taking off.

I expected that meant we’d had an accident and started looking for a wrecked airplane but couldn’t see anything. The specialist said it wasn’t that bad and the pilot had just jumped out of the plane, dragged to carcass off the runway and continued on his way to the spray job.

The pilot had a Twin Comanche that he flew for personal use and during the winter he would travel throughout California and the southwest US. More than once I saw flight plans with arrival times that wouldn’t get him home until after dark. I knew his strip wasn’t lighted and often wondered how that worked.

Finally an opportunity presented itself and I asked him about what happened when he got home after dark. He said he had an “approach” and went on to explain. There was a yard light at the school in the town and he had a yard light at his house and there was a small hill between the field where he landed and his house. He said he lined up the two lights, crossed the school light at a precise altitude at a specific speed and rate of descent. As soon as his yard light disappeared behind the hill he flared and cut the throttle. He then just let the plane roll straight ahead until it came to a stop at the base of his little hill.

Since the guy was in his 70’s I figured it must have worked pretty good for him for a long time and never again worried about what happened after dark.

AIRCRAFT LOST, CONFUSED, IN DISTRESS OR WHAT?

This was before GPS and the majority of the pilots were not IFR rated. Radar coverage over most of our area began around 10,000 feet and navigation aids were a long way apart. The area is sparsely populated and the there aren’t a lot of unique topographic features. The end result of all this was that it was not uncommon to have aircraft become lost (or at least unsure of their position). It was normal for each of us to have 2 or 3 orientations a month assisting pilots in determining their position using the Direction Finder and other orientation procedures. There were also a number of pilots who would have us do practice orientations on a regular basis as well.

He wasn’t lost (but didn’t know where he was)

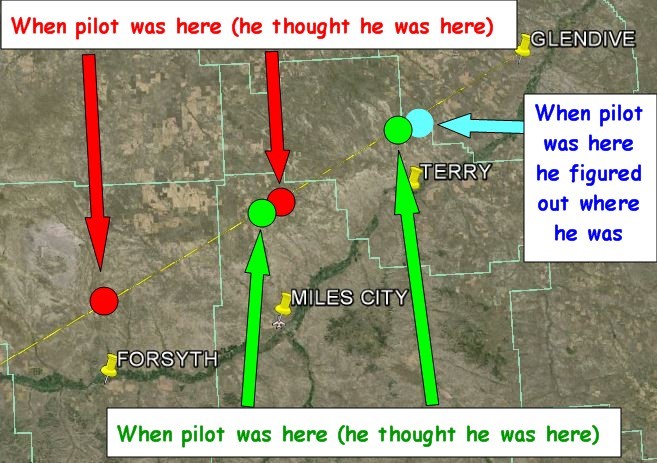

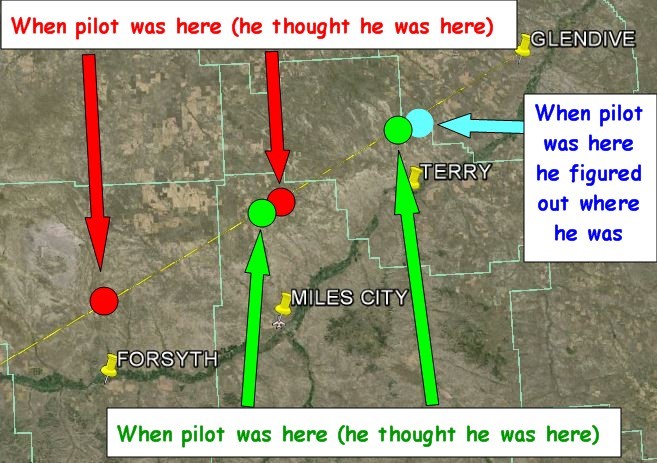

One night an aircraft called, enroute from Billings to Glendive, with a position report. Cities and larger towns in that part of Montana were mostly established along the Yellowstone River, which runs from southwest to northeast. The pilot reported north of Miles City but on my DF he was west. Suspecting he was north of Forsyth (the next town to the southwest) I asked him to confirm his position. He was insistent on where he thought he was saying he could see Terry (the next town northeast of Miles City) ahead. A while later he reported north of Terry, but now my DF showed him north of Miles City. I figured he was one set of towns off and told him what I saw on my DF, but he again insisted that he was north of Terry and could see Glendive ahead. I asked him for a fuel status and he had 3 hours left so I figured that even if he was 50 miles behind of where he thought he was he wasn’t going to run out of fuel and would eventually figure it out.

Sure enough the next call he advised that now he was “really” north of Terry and had the lights of the “real” Glendive ahead.

Who turned this guy loose?

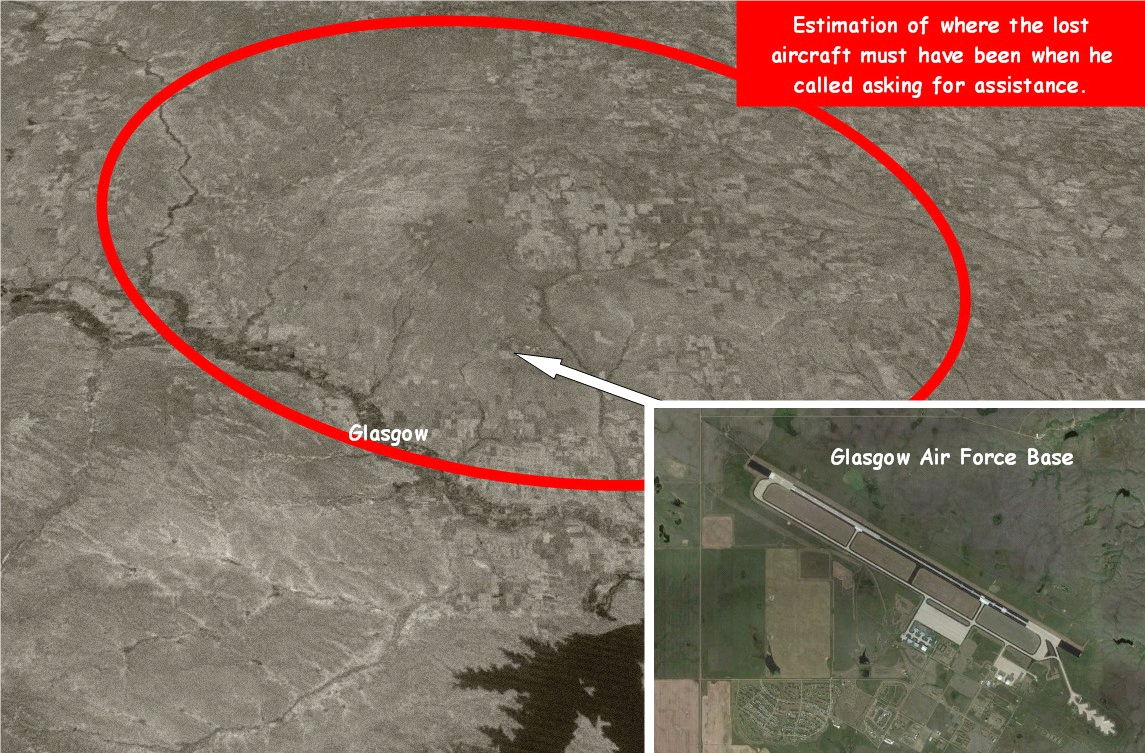

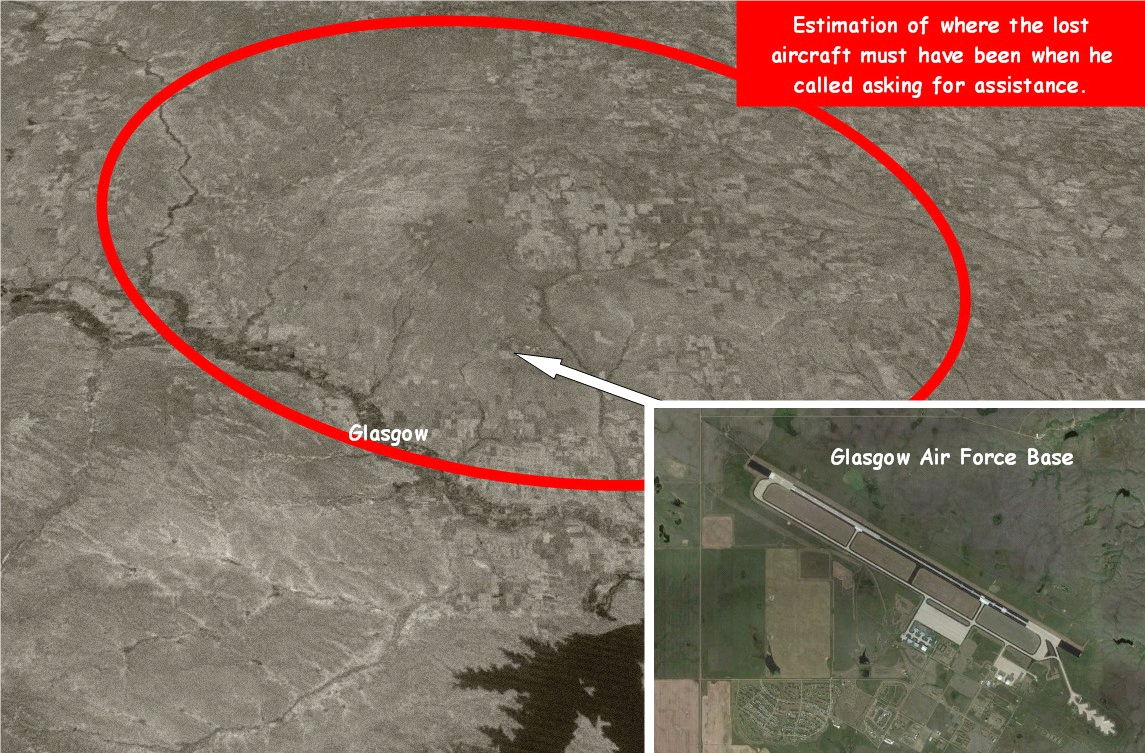

The biggest city in the northern portion of our Flight Plan area was Glasgow, and the Glasgow Air Force Base was located about 20 miles north-northeast of Glasgow. Glasgow AFB had been established about 1957 as a fighter-interceptor base, and in 1961, B-52 bombers and KC-135 tankers began to operate from the base. It was deactivated about 1968 and then reactivated in 1971. By 1977 it was deactivated again and the tower had been shut down, the runway closed, and the only personnel stationed there were caretakers who were closing the place down. One day I got a call from a Piper Comanche with student pilot on a long cross country. He was low on fuel and uncertain of his position. We tried to get him to tune the Glasgow VOR, but he didn’t seem to know how to use his VOR receiver and the information he was giving us didn’t make any sense, so we tried pilotage. There aren’t a lot of unique or significant landmarks across the prairies and wheat field of the area, so that was problematic. He did say he’d seen some white domes, that led us to believe he’d sighted the air force base or a radar station, but he hadn’t seen any runways near them. He couldn’t tell us how long ago it had been or what headings he’d been flying since then. We asked him to squawk emergency but he couldn’t confirm that his transponder was even turned on. We called Salt Lake ARTCC and asked if they had any primary or secondary targets in the area and advised they might be squawking emergency. The controller had only 3 primary targets, none identified, and none were on headings even close to our Comanche.

About that time the guy quit talking to us and we began to shift to a SAR mode thinking he must have run out of fuel and crashed. But we had no real idea of where we would even start the search.

A short time later (it seemed like a “long time” then) we received a call from the FBO in Glasgow who had gotten a call from a pilot who said he had nearly run out of fuel, had landed at Glasgow AFB, and wondered if the FBO could bring him some fuel. I believe our facility manager finally reached him and we figured out that he had turned around without telling us (that’s why none of the radar tracks matched our aircraft) and landed at the air base.

The next day I received a call from an Air Force Major. He said his CO had told him to call and make sure we knew that the base and runway were closed at Glasgow AFB. I assured him we were aware of that and asked if this was a result the Comanche that had landed there the previous day. I was thinking that perhaps they didn’t realize it was an emergency landing. He was astounded and said he had no idea a plane had landed there, he had just been directed to call us and had no idea what had prompted the order.

Not lost but scared and scary

One summer evening shortly before sunset a Cessna 140 pilot came in. He was enroute from Billings, MT to his farm near Bowman, ND. He asked about weather conditions eastbound which were really not a problem, I was estimating 5,000 overcast and visibility was good. He asked if I would be able to use the DF to give him a heading outbound from Miles City to Baker. He had no navigational equipment on the aircraft and his plan was to take the outbound heading that I gave him until he got past the higher terrain east of Miles City. He figured he would be able to see the airport beacon from Baker by then. Once he got to Baker he would be able to see the beacon from Bowman and get home. Even with the good ceilings and visibility I knew it would be dark soon. He wouldn’t file a flight plan and with the overcast, there wouldn’t be any moonlight so I tried to talk him into staying. I even offered to let him use the cot we kept for emergencies and sleep at the FSS. He declined saying that he had to get home. He said he’d been working in the field when his wife left for Billings and realized that she didn’t have all the documents she needed so he jumped in the plane and flew to Billings. Now he needed to get home because there was no one there to milk the cows.

He took off just at sunset, and using the DF I got him headed east. Just when I thought he was on the way, he called to advise that all his lighting had gone out and he was returning to Miles City. I didn’t hear from him again and he wouldn’t answer up on the radio, so after a bit I went outside and observed an aircraft with lights over the field turning towards the east. I called him on the radio again and he said he’d gotten the breaker back in and everything was fine. I suggested again that he might want to stay overnight, but he said no and asked for the outbound heading again.

After he’d been gone a while, and I presumed he was well on his way, I suddenly got a panic call from him saying, “I’m in the clouds, what should I do?” I can honestly say that in 26 years with the FAA this was the one and only time I ever heard pure panic in the voice of a pilot. Anyway, I told him to just concentrate on keeping wings level and throttle back so the plane will settle out of the clouds on its own. A minute later he called to say he was out of the clouds, so I asked his altitude. He was at 7,000 feet (which confirmed my estimated 5000 foot ceiling)!!!! He thanked me, said he would stay at 5500 feet and said goodnight.

This whole thing really bothered me so after a while, when I figured he should have been in Bowman, I called Dickenson FSS to see if they’d heard from him. To my surprise the specialist said he had and, in fact, the guy was sitting in the Dickenson FSS waiting for someone to drive up from Bowman to take him home. It seems that the Bowman airport beacon was out of service (since this was a Local Notam I had no knowledge of the outage). When the pilot got to Baker and couldn’t see the Bowman beacon so he’d turned northeast and had flown to the Dickinson beacon.

I don’t think this guy was ever lost

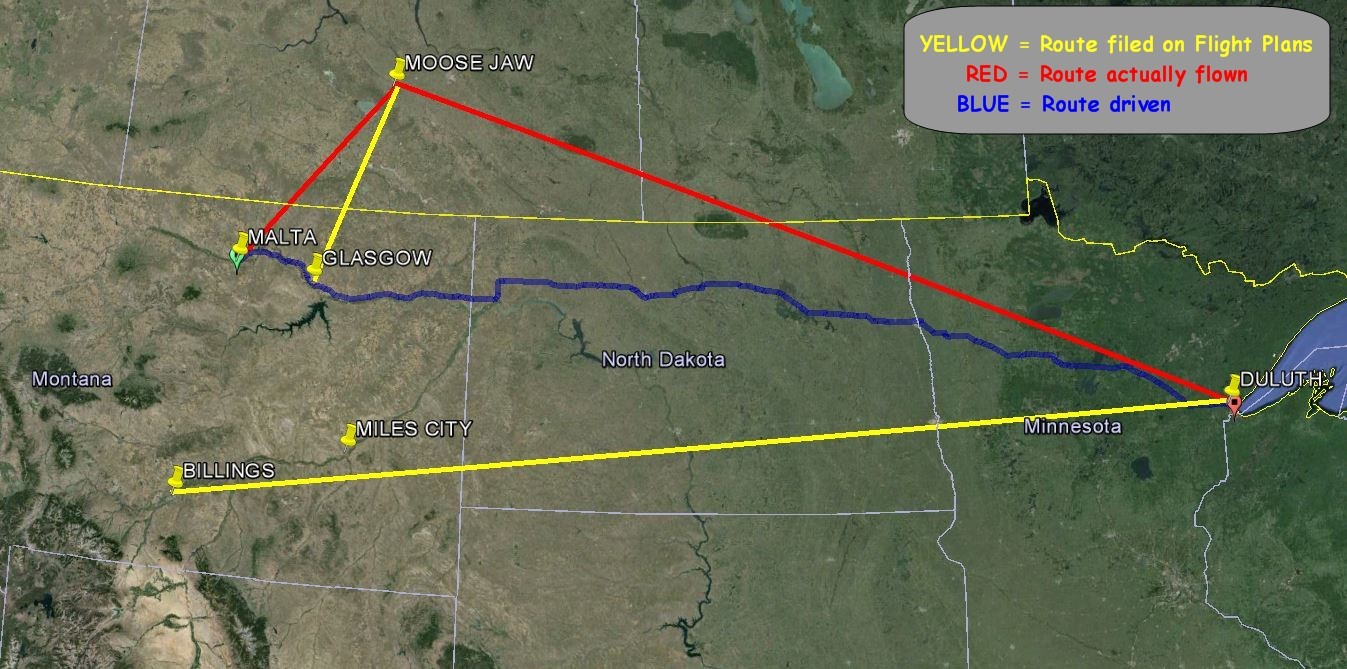

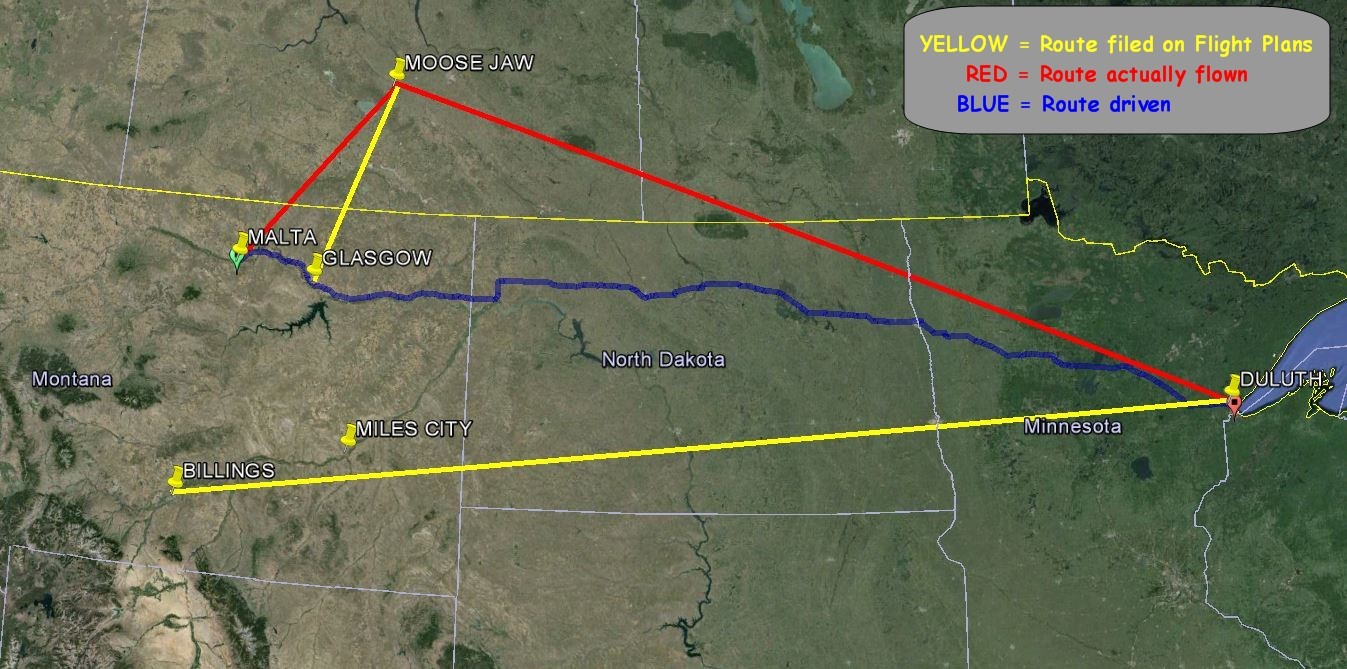

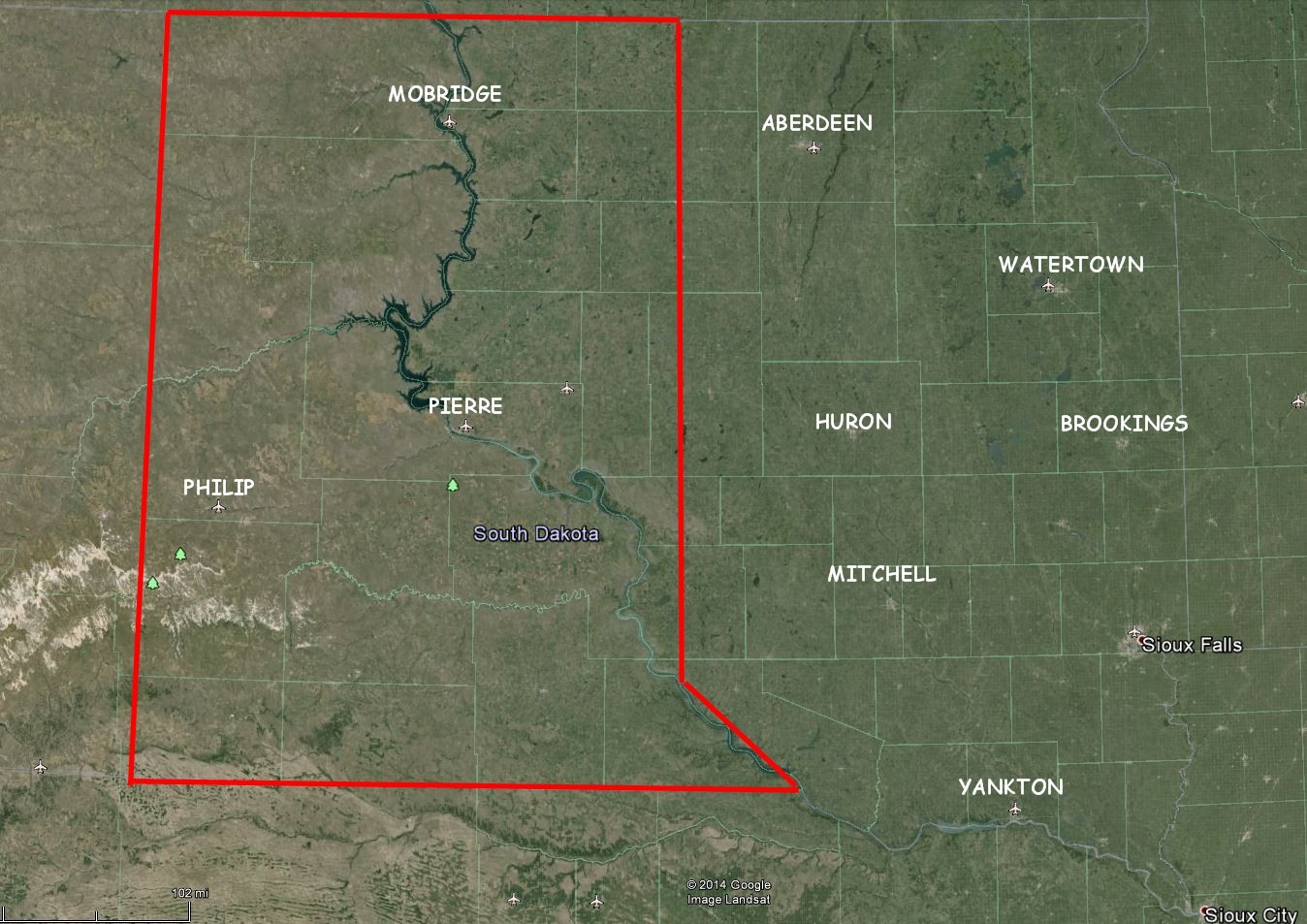

One day I got a call from Billings FSS. They had a Cessna 421 overdue on a VFR flight plan from somewhere in North Dakota or Minnesota. I hadn’t talked with the aircraft, but a short time later I received a teletype message from a FSS in Canada advising that the C421 had gotten lost and landed in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. I let them know that the aircraft was on a flight plan to Billings and called Billings with the information I had.

When I came in the next morning the specialist who had been on the midnight shift advised me that the same C421 had filed a flight plan from Moose Jaw to Glasgow, MT and requested customs. When the aircraft didn’t arrive or cancel his flight plan the specialist tried to call him on the radio and managed to establish contact. He was lost again and declared an emergency. While in the process of trying to locate the aircraft the pilot saw an airport, which turned out to be Malta, MT (about 100 miles west of Glasgow) and decided to land there. Since the aircraft was inbound from Canada, it needed to clear customs, and there was no customs service available in Malta. The specialist told the pilot to stay with the aircraft until someone from a law enforcement agency could meet him. I don’t know the details, or who made the decision, but a State Patrol trooper went to the airport only to find the aircraft parked and no people anywhere.

We subsequently learned that the pilot was from Minnesota; he owned several aircraft but only had a student license that had been issued in the 1950’s. Investigators also determined that the pilot had rented a car and a U-Haul trailer that night in Malta.

I never heard any more about the pilot, but in the early 1980’s I happened to be driving through Malta (my home town is about 90 miles west of Malta) and I stopped at the airport. The C421 was still parked on the ramp and there were chains wrapped round the props!

More disoriented aircraft

One morning just a little before 8:00am, when I was just getting off a midnight shift, an aircraft requested orientation assistance. The specialist who’d come in at 6:00AM took the call so I could complete the shift turnover to the oncoming specialist.

He’d no more than determined the aircraft location when another aircraft called with the same problem. The 0800-1600 specialist, who had just relieved me, took that aircraft while the first specialist finished up with his paperwork documenting the first orientation.

In the meantime I had taken the 8:00 AM weather observation and was about to leave as the second specialist completed that orientation and started doing the paperwork. Before I could leave the room a third aircraft called asking for assistance, and because I was the only one not busy I took him. He said he was on top of the overcast but had encountered a wall of cloud and needed to know where he was. I determined that he was directly over Forsyth, MT (west of Miles City) and he elected to turn back to Billings.

A few days later I talked to the pilot and learned that he’d been there for a while circling as he listened to us work the first two aircraft, “… just waiting his turn.”

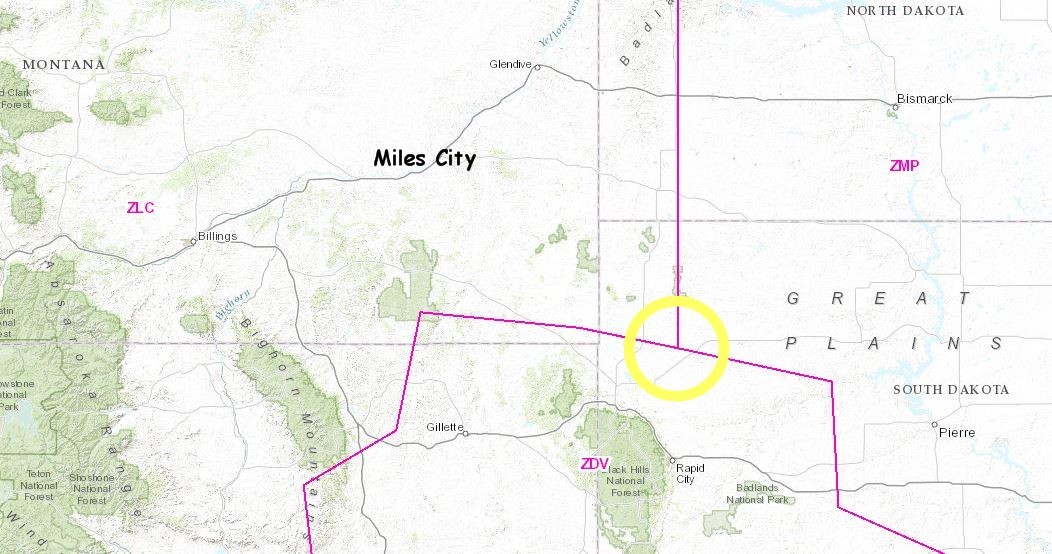

Calling “Any Facility”

During a midnight shift I heard a military aircraft, probably a B52, calling “any facility.” I could tell he was a long way off, we got those calls frequently requesting altimeter settings, so I figured a facility closer to his position would respond. I then noted that the aircraft was calling on the UHF emergency frequency and no one else was hearing him so I responded. The pilot was declaring an emergency due to engine problems, advised that he needed clearance for an emergency descent and gave me his position. It turned out he was in northwest South Dakota very near a point where the airspace of Denver Center (ZDV), Salt Lake Center (ZLC) and Minneapolis Center (ZMP) meet.

Salt Lake Center was the only control facility with which I had direct contact so I called them. The controller advised that he saw the emergency squawk code, but the aircraft wasn’t in his airspace. I relayed the aircraft message and again got a “it’s not my airspace so it’s not my problem” type of response. I suggested he try to coordinate with whoever owned the airspace and then called the aircraft.

The pilot advised that they had started their descent heading for Ellsworth Air Force Base in Rapid City, SD, so I should just let center know to get any traffic out of the way.

I called the controller back, passed that message and this time got a little more reaction. He said he’d call Denver. A few minutes later he advised that Denver center had talked to the aircraft and they were now with Ellsworth approach control.

DF Approach

The DF (Direction Finder) was a wonderful tool. In addition to giving us the ability to get a line of bearing from the airport to use for cross fixes, we had the ability to guide the pilots on “last resort” (very) non-precision approaches. I personally only know of one time this was done for real, but it worked exactly like it was supposed to.

There were three pilots who owned an aircraft in Colstrip, MT and periodically they would fly up to Miles City and ask for practice DF approaches. One of them told me that they were not instrument rated but it was good practice for them to come up to Miles City, where the airspace wasn’t too busy, and have us give them approaches while they took turns flying with a hood.

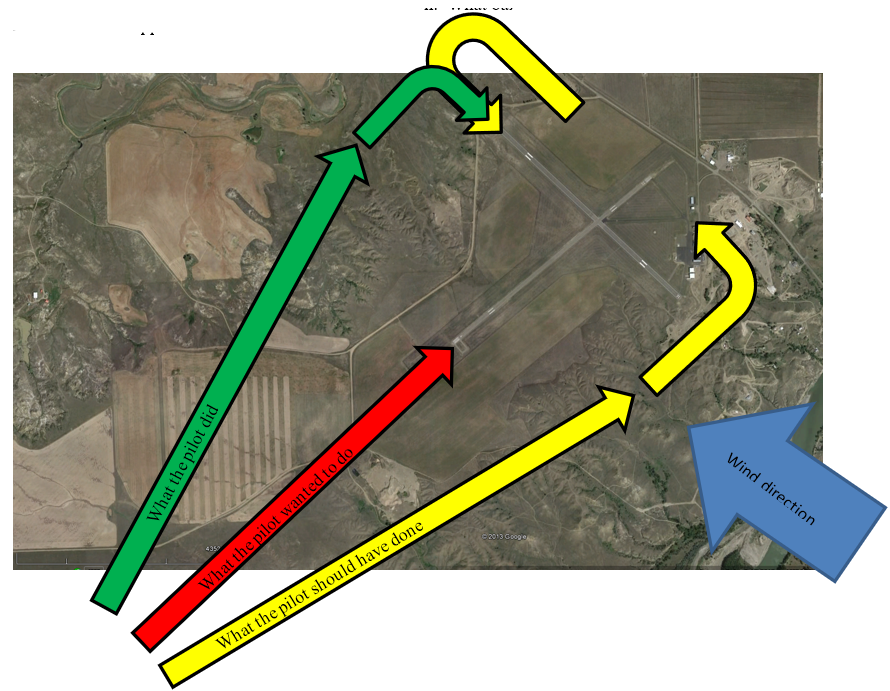

One Saturday or Sunday they called in and asked if I had time to do some approaches. The weather was good except there was a very strong cross wind to the final approach course.

Well the first pilot flew his approach and everything was working pretty well until he was lined up on final. The heading I gave him failed to compensate enough for the crosswind and when he finally broke off on the approach he wasn’t even close to the runway, in fact he was barely over the airport.

The second pilot flew his approach and I gave him a heading to fly that I figured would work with the wind. He was close enough to the runway that he would have been able to land in a real emergency, but I thought I could do better.

By the time the third pilot turned on final I thought I had the necessary correction figured and sure enough he was coming straight in to the runway. I was feeling pretty proud of myself when all of a sudden he started to drift big time. He was too close to the airport to make any corrections so I terminated the approach and they landed. I couldn’t imagine what had happened; I was sure I’d given him enough correction and there hadn’t been any significant change in wind since the two previous approaches.

They came into the FSS after they landed to debrief and I apologized but said I had no idea why the last approach went so bad at the last minute. They laughed telling me that it was the pilot – he’d “lost the picture” and the safety pilot had to take the aircraft to complete the landing.

ACCIDENTS AND INCIDENTS

The Mail Mess

The contract carrier who brought the mail to the airport each evening, and picked it up each morning, developed a pretty good relationship with the regular pilots on the mail plane. Apparently they’d developed a procedure by which the carrier would place the mail bags on the ramp and the pilot would shut down his left engine as he taxied in and straddle the bags as he rolled to a stop. One night a relief pilot was on the trip and didn’t get the engine shut down soon enough so the prop was still windmilling as he rolled up on the mail bags. One of the props hooked the mail bags, tore them open and threw mail everywhere. People were running all over the place collecting bags and bits of mail for the next hour!!

Carb ice – Really?

Working one evening in the winter I had a call from an inbound Cessna. I gave him an airport advisory and continued with other duties. After what should have been enough time for him to land, the other specialist and I realized he’d never reported clear of the runway. It was too dark to see anything on the field, and we were expecting a call from the scheduled commuter flight soon, so we were a little bit concerned.

Just then the Cessna called and asked if we could reach the FBO and have them bring some de-ice fluid out to the runway as he had some carb ice and the engine had quite on the runway.

We made a call and the FBO line service kid drove out to the runway. He wasn’t there very long and then came back to the ramp. He stopped at the FSS to advise that he would be going back out with a tug… the Cessna engine had quit because the plane was out of fuel.

Good planning (not)

It was a nice summer day, a little busy with 3 or 4 aircraft constantly in the pattern, when a Twin Comanche with a Canadian registry called and asked for a DF steer to the airport. He was on a VFR flight plan inbound from Great Falls (northwest of Miles City) but the DF showed that he was southwest of Miles City. Apparently, when he saw the Yellowstone River, he knew he’d missed the airport and was flying up the river to find us.

Winds were from the southeast favoring runway 12, but not very strong. The way the traffic was working out I figured the Twin Comanche could probably enter the downwind leg for runway 12 about midfield and land runway12, but he asked if he could land straight in on runway 04. I again alerted him to the traffic and suggested he might be able to make a right base to runway 12 if the other traffic would cooperate, but it was an uncontrolled airport, so it was his decision.

He elected the right base option and landed on runway 12 uneventfully but I learned later from the fueler that there was probably less than 5 gallons of gas remaining when the aircraft landed. That was undoubtedly the reason he didn’t want to fly the standard left hand pattern. What baffled me was why hadn’t he fueled in Great Falls when he stopped to clear customs.

The Mail Plane Accident

Kris, the pilot who flew the AC50 mail plane was also the airport manager in Wolf Point. As a result, I became fairly well acquainted with him. At some point Kris bid on the mail contract in competition with the company that he was flying for, and as a consequence he was fired. The new pilot who was brought in was a nice enough guy, but I never really got to know him.

During the winter of 1977 I’d gone to Havre for a long weekend. As I left Havre, heading back to Miles City, I heard a news report on the radio that a mail plane had crashed north of Miles City. The name of the pilot had not been released, and knowing that Kris occasionally filled in on the mail flight, I was concerned he might have been flying.

As I traveled east I eventually got within range of the radio station from Wolf Point. They were reporting the story and giving the name of the pilot. It wasn’t Kris, it was the new guy.

That afternoon when I got to Miles City I received a call from my brother, who, at the time, was a reporter for the Great Falls Tribune. He wanted details about the accident and the name of the pilot. I told him that, even if knew anything, I couldn’t give out information but regardless, I’d been in Havre and had just gotten back to Miles City. I couldn’t even remember the pilot’s name so I told him to call the radio station in Wolf Point because they were putting the name out.

The next day I saw the story in the Tribune and they’d spelled the pilot’s name incorrectly! Later when I talked to my brother he said he’d called the radio station and gotten the correct name, but when the Associated Press released the story they had a different spelling so the editors decided to go with the version in the AP release!

PEOPLE AND THINGS

The summer aide

During the 1970’s the FAA had a program to hire high school kids during the summer to help out at the facilities. I think it may have been titled “stay in school” or something. The first two summers I worked at Miles City FSS we had a high school girl who helped with filing, etc. She graduated, and for the third summer, upper management advised that anyone hired had to be a minority, and being female didn’t count. Native Americans were about the only minority in southeast Montana. Our summer aid in 1977 was a high school dropout, about 16 years old, who was half Japanese and half Native American.

His transportation, when he started, was a small motorcycle or scooter but as soon as he had a couple of pay checks he bought a car. I don’t recall seeing that first car, but I was told that the FSS specialist who first saw it called the dealership and told them they’d better give the kid his money back or give him a better car, or they’d never see anyone from the FAA in their showroom again. So he got a “better” car. This one I saw… the windshield was cracked, it had a coat hanger for a radio antenna, the tires were not quite bald, and there was always a large puddle of oil wherever it was parked.

I know at least one of the specialists talked to the kid about the oil leak and I believe they had something scheduled with the dealer to look into that. Then one Monday the kid was late for work and it turned out he’d had to walk to the airport. His story was that he’d been driving the car and all of a sudden the heat gauge shot up, the engine went “klunk,” and it quit running.

It turned out that although they had talked with him about the oil leak, no one thought to tell him he needed to replace the oil that was leaking. He’d driven the car until all the oil was gone and the engine seized. He didn’t really have money to fix the car so he got his motorcycle back and started driving it to work every day.

A week or two later we were talking at work and he mentioned that he and his friend had been in his car listening to the radio. That seemed odd and I asked if he’d gotten it fixed. He said, “No, it still won’t run, but it’s only 6 blocks from our apartment so we walk down to where the car is and listen to the radio at night.”

The sheep herder

One day, as I recall, it was a weekend afternoon during the first spring I was in Miles City, a guy walked into the FSS. I was working with Steve Martinez, one of the best specialists I ever knew, and Steve kind of took the lead in talking with this guy. The three things I remember about him were that his clothes were filthy, he smelled horrible, and he was irate.

He demanded that we tell him the name of the pilot of one of the spray planes that operated from the field. He didn’t know what plane it was and wasn’t even sure what color it was, but he wanted to know who the pilot was because the plane kept flying low over his sheep camp and scaring his girlfriend.

It was difficult to keep from laughing because this guy was so dirty and smelly we couldn’t imagine that he could have a girlfriend, or if he did, what she would be like. The problem was that the guy was scary mad and when we finally got him out of the facility, he said he was going to sit there in his pickup until he saw the plane, then he was going to kill the pilot.

We’d noticed that he had something shoved down his pant leg that was long and stiff, and as he walked across the parking lot we could tell it was long enough that he couldn’t fully bend his leg. Thinking that it could easily be a rifle or shot gun, and given the threats he made, we decided to call the sheriff’s office. In a few minutes a deputy pulled up and started talking with the guy. It turned out that he had a tire iron in his pant leg, and we observed the deputy handcuffed the guy, but we never heard any more about it.

Midnight visitors

The airport at Miles City is about two miles north of the city (about 3 miles driving distance) on the bench above the Yellowstone River, and at night the Flight Service was the only lighted building on the airport. Consequently, we got the occasional odd visitor.

One night I had four teenagers walk in the airport ramp entrance. There wasn’t any aviation activity so I was somewhat startled. It seems they’d been out driving around on a gravel road on the other side of the airport when they ran their car in a ditch, or it broke or something. They saw the lights across the airport (about a mile) and walked across the airport to call for help.

Another night, in the dead winter, with temperatures near ten below and a steady wind, I heard a rapping at the employee entrance door. Intrigued, because the door wasn’t locked, and anyone having business there would have just walked in, I went to see what was up. My midnight caller turned out to be a truck driver – wearing nothing but a long sleeve shirt and a quilted vest. He said his truck had broken down a couple of miles up the road and he was walking into town! He just wanted to warm up a bit before continuing into town. I couldn’t believe that he wasn’t frozen. I got him to accept a cup of coffee and offered to call a cab. He thanked me for the coffee, declined the cab, and after warming up for about 15 minutes, he left to walk the rest of the way into town.

They’re watching me

Miles City was a small town, and aside from a small VA hospital, there weren’t many federal government employees in town. During orientation the facility manager pointed this out and told us that as a result, many people would just see us as the government, and we needed to keep that in mind in our interactions in the community.

One of those interactions was with an older lady that would call every month or two. She’d apparently been doing this for some time because after I first talked to her, the other guys all knew about her, it was kind of a “rite of passage” to have to deal with her. She was looking for help because “they” were watching her and tapping her phone. She was unclear about who “they” were but when we suggested that she call local police, the sheriff or the FBI she’d tell us that she couldn’t because they were all in on it.

She eventually quit calling. We always wondered if “they” got her.

The story behind the story

One really hot summer Saturday afternoon a C310 from Glasgow landed and parked right in front of the Flight Service Station. The plane belonged to 3 brothers who had businesses in Glasgow. I didn’t know that much about them but believe one had a beer distributorship, one was a grocer, and the third had a furniture store. We talked to them now and then but they didn’t fly all that often and I’d never met them. As they got out of the plane one of them got a small suitcase or briefcase out of the baggage compartment and another pulled out a case of beer.

They came into the facility and we talked about the expected weather for the rest of the afternoon, and they said they wanted to leave the plane where it was parked. That was no problem and they left to hop in a car that had pulled up in the parking lot. After they got out the door I noticed that they’d forgotten the beer so ran out and told them. They responded, “What beer?”

Since we had only four specialists all that summer, the beer was easily divided, but I couldn’t imagine why they’d do that. We just didn’t deal with them that much and when we did it was all very business-like with no sense of familiarity or friendship. It was nearly 10 years before I got an answer.

In 1987 or 1988 I was in Watertown, SD FSS as the area supervisor and was looking through old documents in the files when I found a report of a successful aircraft orientation/save accomplished by a Watertown specialist. It involved a C310 enroute to Glasgow, MT, that had gotten caught in an area of rapidly developing thunderstorms and became disoriented. The specialist determined the location of the aircraft and assisted them in finding a suitable airport to land. I cross checked the tail number and it matched up with the businesses in Glasgow!

The Crew Car

Miles City is located in farming and ranching country. One of the implement dealerships left a courtesy car at the airport and we kept the keys in the FSS. Our instructions were that it was primarily for farmers and ranchers who flew in for parts, but we could let it out to anyone who asked use it.

It was a well-used, 10-15-year-old Dodge that ran OK but had transmission problems and sometimes brake problems. I recall one pilot bringing it back and reporting that the car had nearly killed him. The transmission was slipping and he said he was crossing the railroad tracks when it happened. A train was coming and he was barely able to lug it out of the way!

One day in late August the keys disappeared. It had been used a lot (it was harvest season) and no one knew for sure exactly when the keys disappeared, so we figured someone had forgotten to return them but had no idea who it might have been.

Winter set in and the car was literally buried under a giant snow drift, made worse by the snow berm the plows had pushed up against the car. Then one day in February, someone found the keys while cleaning out a drawer. We called the dealership and told them we’d found the keys, thinking they’d be happy to know we found the car and that it would again be usable when the snow melted. Temperatures were well below zero and it didn’t seem like there’d be any immediate need to dig it out or to get it running.

About an hour later we were surprised to see 3 guys show up with shovels, and watched as they began digging the car out of the snow drift. As we watched we speculated on whether they planned on towing it away or what they had in mind. Since it hadn’t been moved for close to 6 months we figured it was pretty much dead.

Once they had the snow mostly cleared off one of the guys came in, got the keys, climbed in the car, and to our amazement, the car started on the first try. They finished digging through the drifts while the car warmed up and drove it away. And they never brought it back.

Harry

Harry was a retired Air Force Colonel who flew for the FBO in Miles City and also was the contract pilot for a C421 owned by a trucking company in Miles City. The first few times I encountered him I thought he hated me. He’d come into the flight service, refuse any help, and look at weather printouts and charts on his own, and then fill out his own flight plan. Finally one of the “old timer” specialists, who he talked and listened to, clued me in that it was just that I was a new guy and would have to earn Harry’s trust.

Harry lived across the street from our Airway Facilities manager, George. One day I was with another specialist, Rick, and we had to stop by George’s house so Rick could pay his daughter for babysitting. After that was taken care of George, Rick and I were sitting on the front steps drinking a beer when Harry came home. He invited us over for “a drink” that turned into a long evening on his patio in the back yard.

As the evening wore on one of George’s kids came over and took George home. Then Rick laid down on the picnic table and went to sleep. Harry and I continued drinking and telling stories – his about the Air Force, mine about the Navy.

After that night Harry treated me like the other “old timers” and we had a great relationship.

There was a VA hospital in Miles City and from time to time the Miles City FBO would fly patients to other hospitals. On one occasion, Harry was taking a patient to Salt Lake City, and while he was filing his flight plan, he invited one of us to ride along. Somehow I was able to go. The patient had some kind of infection in a leg and Harry said he’d already had a couple of operations and it was likely they would have to amputate the leg. The guy was, under no circumstances supposed to get on his feet.

When we arrived in SLC the ambulance that was supposed to meet us wasn’t there and Harry told me to stay with the plane and patient while he went to see what was going on. Well, I had to pee like a racehorse and it seemed like it took forever before Harry got back. I presumed he had, among other things, taken the time to relieve himself before returning to the plane.

When he finally got back he was disgusted that the ambulance hadn’t even been dispatched and he said we needed to get the patient up so he could use the rest room. We walked him into the FBO so he could take care of business and by the time that was done the ambulance had arrived. I immediately made a bee line to the rest room and surprisingly Harry was right behind me… he also had put the patient ahead of his own needs!

At Christmas time, the first year I was in Miles City, we all received a fifth of whiskey. I was told that it “just showed up” and no one really knew where it came from. I thought maybe the manager bought it and didn’t want it to be public knowledge. During November of 1976, my second year at MLS, I overheard Harry questioning the facility manager about how many specialists were working at Miles City. A few weeks later a case of whiskey was found on the doorstep with the same number of bottles as specialists. It turned out that the trucking company that Harry flew for had him drop the stuff off on our doorstep each year. In 1977 when one of our specialists (who didn’t drink) was being transferred he gave me four bottles of whiskey that had never been opened!

The aviation community is pretty small

One winter day I was off duty and running errands in Miles City. The weather was weird – there was no wind in town but the sky was obscured by blowing snow and ice crystals. Since I had nothing better to do I decided to drive up to the airport and see what was going on. Miles City is located on the Yellowstone River and the airport is on the bench about 300 or 400 feet above the town. As soon as I got to the top of the hill I encountered very strong winds and near blizzard conditions due to blowing snow.

As I drove onto the airport I noted the Frontier Airlines commuter, a DH6 Twin Otter, taxing in to the ramp from the runway. When I walked into the facility I saw the plane was turned around and was taxiing back towards the runway. It turned out that the movement surfaces were so icy and the wind was so strong that the plane couldn’t steer and kept turning into the wind. They finally brought a fire truck out and tied onto the nose gear so they could get to the ramp.

There were a handful of light aircraft that had gotten caught by this storm and I think it took a couple of days before they were able to leave. One night during this period I was eating out at one of the local restaurants and overheard the people at the next table talking about their bad luck getting stuck in the storm. One made the comment, “I can’t believe we have to spend another night in Miles City.”

30 years later, after I’d retired from the FAA, I was working as a dispatcher for a charter company in Wenatchee, WA. One day I was talking with one of our mechanics (who was also a pilot) about experiences while working in Flight Service and I related the above story. It turned out that he was one of the pilots stuck in Miles City that week and remembered making that comment at the restaurant!

A lot can happen if 6 weeks

In the late spring of 1978 I was given a temporary promotion to fill in as acting manager for about 45 days, from the time one manager departed until the new manager arrived. I was surprised, as I had less than two years of experience, but appreciated the confidence they had in me. It was spring going into summer, a fairly busy time, and it sure seems like a lot of stuff happened.

I’m a star

The population of Miles City was around 9,000 people but we had a local TV station operated by an old guy, Dave, and his wife. They would hire young people trying to break into broadcasting and pay them next to nothing to handle the camera duties. I was told it was the smallest NBC market in the country. They only had one camera and would use it in the studio for news and local programming, and then when network programs were airing they would take the camera out to record things.

I’d first met Dave during the spring of 1976, with less than a year experience in Miles City. I was alone one evening when someone walked in the back door and went straight into the maintenance work area. I went back to see who it was and found this guy removing one of the oscilloscopes from the equipment rack. He told me who he was and that the manager of Airway Facilities let him borrow equipment to tune the transmitter for the TV station! I figured it must be true, who could make that up? It was true!

While I was acting manager they called and asked to do a program on the FSS. I cleared it with the Regional Office, and one day Dave arrives with his camera and camera man. After some shots around the facility and a short discussion they started to interview me on camera. While we were talking the commuter (Frontier Airlines) called inbound. As soon as the call came in Dave jerked the microphone away from me and tried to catch the airport advisory being given by the in-flight specialist. Dave then began interviewing the specialist who was explaining where the aircraft was and what an airport advisory was. While they were talking the aircraft called again so I grabbed the side mic to answer them and, immediately, the TV mic was back in my face.

Dave then asked where the aircraft would land and I advised they intended to land on runway 12 (the approach end of the runway is the furthest place on the field from the FSS) which was straight away to the west-northwest but about a mile away. Dave tells his cameraman to move the tripod closer to the window so they can get a shot of the aircraft landing.

In the finished program, at this point the picture went all bumpety-bump as the camera was moved, then focused on the horizon to the northwest. If you know what to look for you could just see a speck as the aircraft landed, and then as it taxied, it turns into an airplane.

The good news (for me) was that apparently no one watched the program. At least no one ever mentioned that they saw (or laughed) at me when I was on TV.

There’s nothing you can tell me

A couple of times I ran into specialists who had an especially high opinion of themselves. One such guy was assigned to Miles City in 1977. He went through training in Oklahoma City and returned to the facility for final check out and sign off during the period when I was acting manager.

In those days it was virtually a requirement that prospective employees had some background in aviation. They usually got a month or longer facility orientation prior to receiving a class date at the academy, and the training at the academy generally produced a specialist who was “ready to go” as soon as they returned to the facility. There was a legality that new specialists take weather observations under supervision for 2 weeks before they were eligible to be “signed off” and work alone. Whether we had an exceptional group, or were just lucky, all of the guys I worked with were signed off at the 2-week milestone.

Roy had been an Air Force controller and a tower chief and the FAA was a second career for him. During the orientation and post academy training he always had presented the attitude that our facility was small potatoes compared with what he’d done and there was nothing we could tell him that he didn’t already know.

He was very proficient and capable and as soon as the two-week weather observation probation had elapsed, I sign him off to work alone. The slot in the schedule that he went into meant that he’d be working his first shift alone from 4:00 PM to Midnight on a Friday. And it just so happened it was “Bucking Horse Sale” weekend.

One of Miles City’s claims to fame is the annual Bucking Horse Sale in the spring of each year. It’s essentially a big time rodeo where rodeo producers come to evaluate and buy bucking horses for the rodeos they will produce during the year. It’s also a huge party.

One of my co-workers, Rick, and I had spent the day at the rodeo and returned to my house about 6:00 PM to get cleaned up with the intention of doing some bar hopping. We figured that as long as we were near a phone we should see how the new guy was doing. Rick made the call and what I heard was sort of like, “How’s it going?…really?…uh ha… geeze…damn… oh geeze…OK.” CLICK… “Jim, put a shirt on we have to go to the airport NOW!”

When we got to the airport we found him overwhelmed. There was an aircraft who was unsure of his position and requesting assistance, 2 aircraft overdue into our airports, a message from another facility requesting information on an aircraft that was overdue on a flight from our area, and a good number of aircraft in the airport area. Both phones were on hold with pilots waiting to file flight plans, several flight plans that needed to be filed, and 2 pilots were at the counter waiting for service.

I can’t recall ever hearing of anyone having that much happen at once and getting that far into a hole. With Rick and me helping it took a little over an hour to get everything back to normal.

The guy never had an “attitude” the rest of the time he was at Miles City and, in fact, went on to be one of the better instructors at the FAA academy.

I want to quit

A couple of weeks after Roy signed off another new specialist named Bob, who returned from the academy and did his 2 weeks taking weather observations, I signed his card. He was also retired Air Force and had been a tower chief. He was a really nice guy and while he knew his stuff he never assumed he knew everything. His first week working shifts alone was uneventful and I wasn’t aware of any problems.

Then one evening he called me at home and asked if he could stop by. When he came to the door he told me he wanted to resign and handed me a completed government form. I’d never seen the form before but I guess it was the form that you used to resign. I begged off saying that as the acting manager I had no idea what to do with something like this and asked if he would consider waiting until the new manager got to town in a little over a week.

He was agreeable to that and we never did talk about it at work.

When the new manager arrived I had a few things to talk about – as the next story will illustrate – so I arranged a meeting as soon as he got to town. We met in the lounge at the motel where he was staying and over a couple drinks I filled him in on people and events. He said he’d talk to Bob at the first opportunity. Bob, in the meantime, had changed his mind so by the time they had their meeting, there was nothing to talk about. I still had no idea what had happened.

Several months later Bob and I were working together and he told me that when he first started he was scared to death that something would happen when he was on shift alone and he wouldn’t know what to do. I asked him why, after being a tower chief, he would feel that way, and he said that even as a tower chief there was always an officer on duty who was responsible for tower operation and decision making. He said it took a few weeks before he realized how much he knew and felt confident. While he didn’t say it, I believe that asking him to wait before resigning had been exactly the right thing to do.

How much is enough?

A specialist had started a few months before I became acting manager. He was Hispanic and had been a controller at Denver Center but decided he’d rather work in Flight Service. He was a little “different” and on one occasion he told me the reason he left the center was because they wouldn’t let him sleep on the midnight shift. Interestingly, I ended up training with him and on the midnight shift and even in that position he seemed to have a hard time staying awake.

So anyway, as acting manager, I came to work one morning and learned that he had gone to Denver on his days off and had called a Miles FSS specialist during the midnight shift to let him know that he wouldn’t make it in for his 4:00PM shift that evening. It seems he had ridden his Harley to Denver (a little over 500 miles) and had developed a boil on his rear end that needed to be lanced. He assured the specialist that he’d be there the next day for his 2:00 PM shift. I juggled staffing to cover his shift.

The next morning I came in and learned that he’d called again and, while he had the boil lanced, his butt hurt too bad to ride his bike so he wouldn’t be in for his shift. He assured the specialist that he’d be in the next day for the 8:00 AM shift. I didn’t need to adjust the schedule but the evening specialist had to work alone and I was starting to get a little upset.

The next morning I came in and learned that he’d called and said that it still hurt too bad to ride, but he’d be in for his 6:00 AM shift the next day. I was starting to get really steamed. He’d gotten to the point that he didn’t have any sick leave or vacation time left – in fact he’d used advanced sick leave to the point that he couldn’t earn enough to catch up in the calendar year. I found a management handbook and started looking at options.

Sure enough the next morning I came in to find that he hadn’t shown up for his 6:00 AM shift. He had called to say that he’d overslept and since he couldn’t get to Miles City in time he’d just ride up during the day and work his midnight shift.

Not knowing what procedures to follow or what options I had, I called the Regional Office for guidance. Initially it was suggested that I make him Absent Without Leave (AWOL). Then the guy at the RO had a thought and said, “Isn’t he the Hispanic guy? We’d better just call this Administrative Leave.” This of course meant that he was given the time off without being charged for any of it.

A few weeks later, when the new manager arrived, he had a talk with the specialist. I don’t know what was said but the guy’s performance improved noticeably and there were never any attendance problems the rest of the time I worked at Miles City.

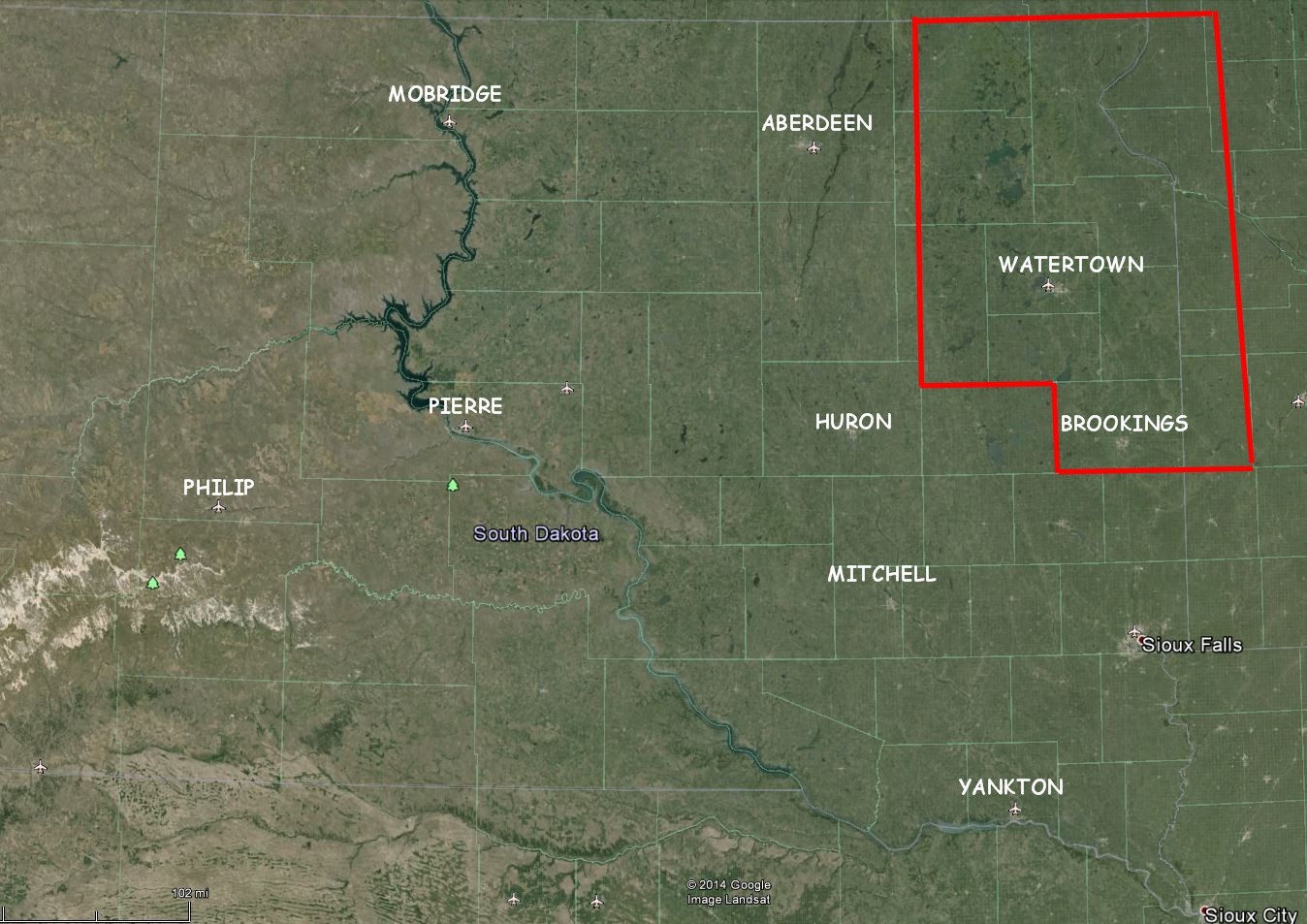

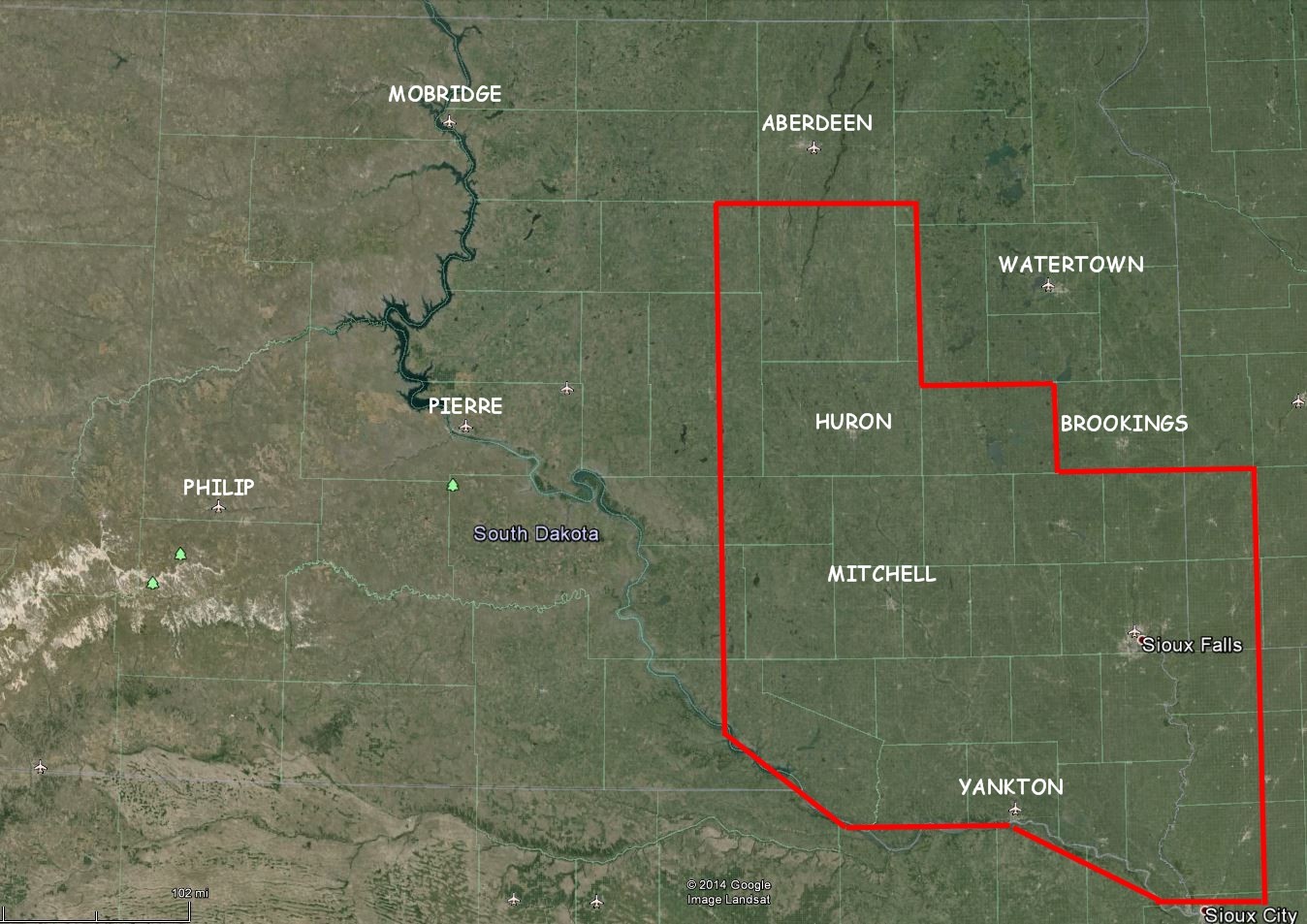

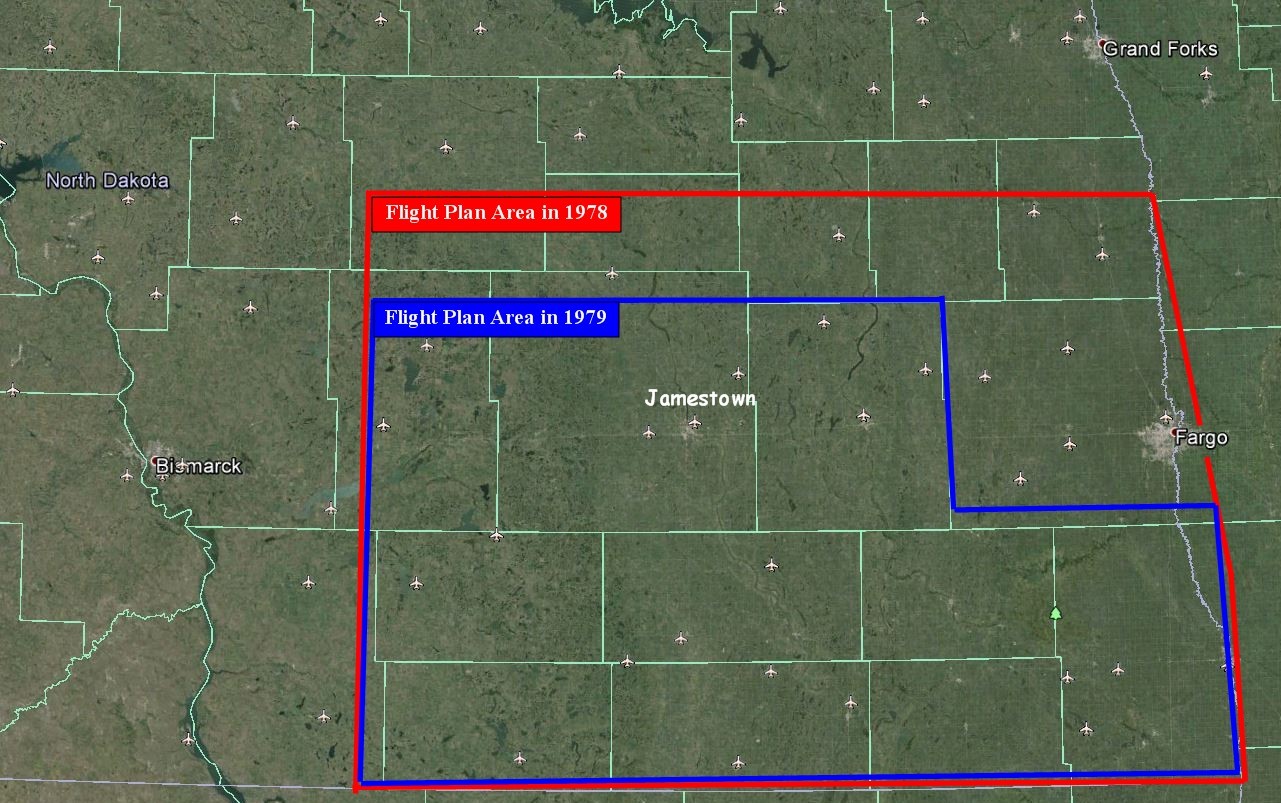

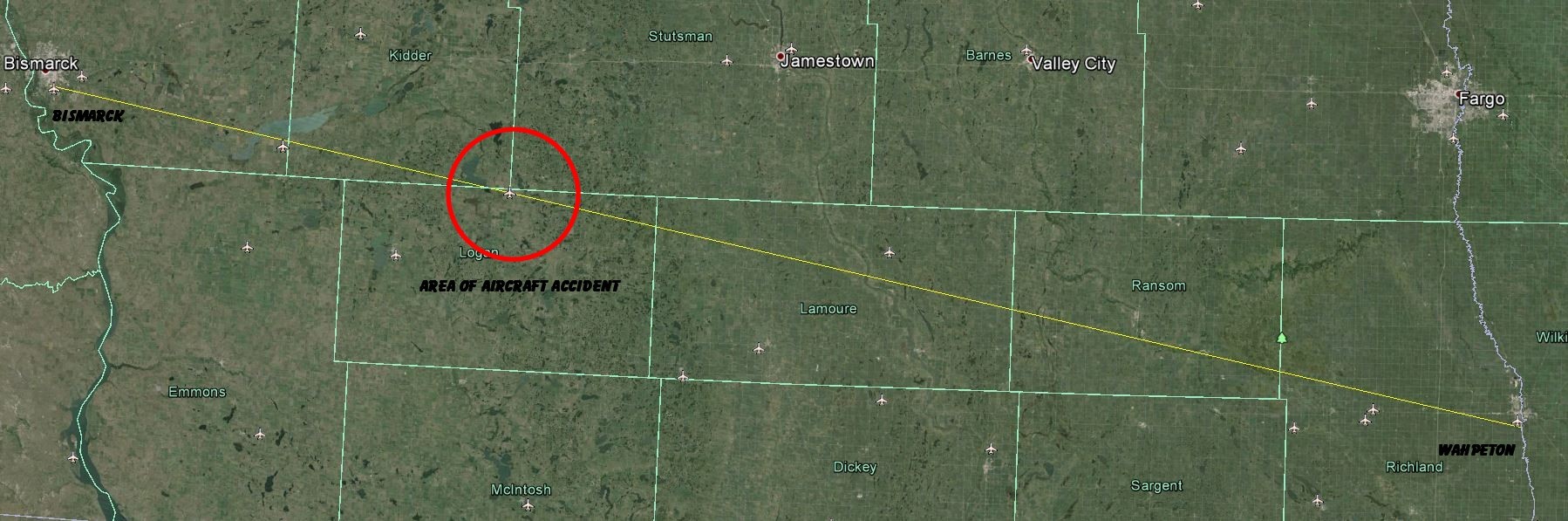

Northwest Airlines was flying B727s through Jamestown when I started working there. There were two runways, 12-30 and 04-22 (which is basically shaped as an X) but only runway 12-30 was constructed to handle the weight of a B727. Also, the only taxiway that the aircraft could use was from the intersection of the two runways to the ramp. Our standard policy was to broadcast a reminder for the pilots to not turn off the runway but to taxi back down the runway to the intersection then to the ramp.

Northwest Airlines was flying B727s through Jamestown when I started working there. There were two runways, 12-30 and 04-22 (which is basically shaped as an X) but only runway 12-30 was constructed to handle the weight of a B727. Also, the only taxiway that the aircraft could use was from the intersection of the two runways to the ramp. Our standard policy was to broadcast a reminder for the pilots to not turn off the runway but to taxi back down the runway to the intersection then to the ramp. A mail plane came through Jamestown every night enroute from Fargo, ND to Bismarck, ND and return during the midnight shift. They used Beach 18 aircraft that had seen better days. Their radios were so bad that when you heard some kind of scratchy squelch break at about the right time of night we just automatically gave them an airport advisory.

A mail plane came through Jamestown every night enroute from Fargo, ND to Bismarck, ND and return during the midnight shift. They used Beach 18 aircraft that had seen better days. Their radios were so bad that when you heard some kind of scratchy squelch break at about the right time of night we just automatically gave them an airport advisory.

The aircraft had all kinds of instrumentation and they would simultaneously fly (at different altitudes) into clouds that were developing into thunderstorms to sample conditions. Support personnel on the ground included a meteorologist and a bunch of scientists. They had an early generation Doppler radar system and a large array of rain gauges spread over several thousand square miles in southeast Montana. Data from the aircraft, radar and the precipitation readings from the rain gauges were collected and studied.

The aircraft had all kinds of instrumentation and they would simultaneously fly (at different altitudes) into clouds that were developing into thunderstorms to sample conditions. Support personnel on the ground included a meteorologist and a bunch of scientists. They had an early generation Doppler radar system and a large array of rain gauges spread over several thousand square miles in southeast Montana. Data from the aircraft, radar and the precipitation readings from the rain gauges were collected and studied.