A personal history written and submitted by Jim Anez, Huron Flight Service

Jamestown was on the verge of being downgraded from a Level II to a Level I facility and we had more specialists than there was work for, so I asked for a transfer. My choices were Great Falls, MT or Huron, SD, and we decided on Huron. We moved at the beginning of August two weeks after our son was born. The transfer was scheduled for early in July, but the FAA was good enough to delay the move until after the baby came. It wasn’t much fun staying in a hotel for 30 days with 7 and 9-year old’s, and a newborn, but we managed. In about 1983 I got a Flight Watch position and, in the fall of 1985, I was selected as supervisor at Watertown, SD.

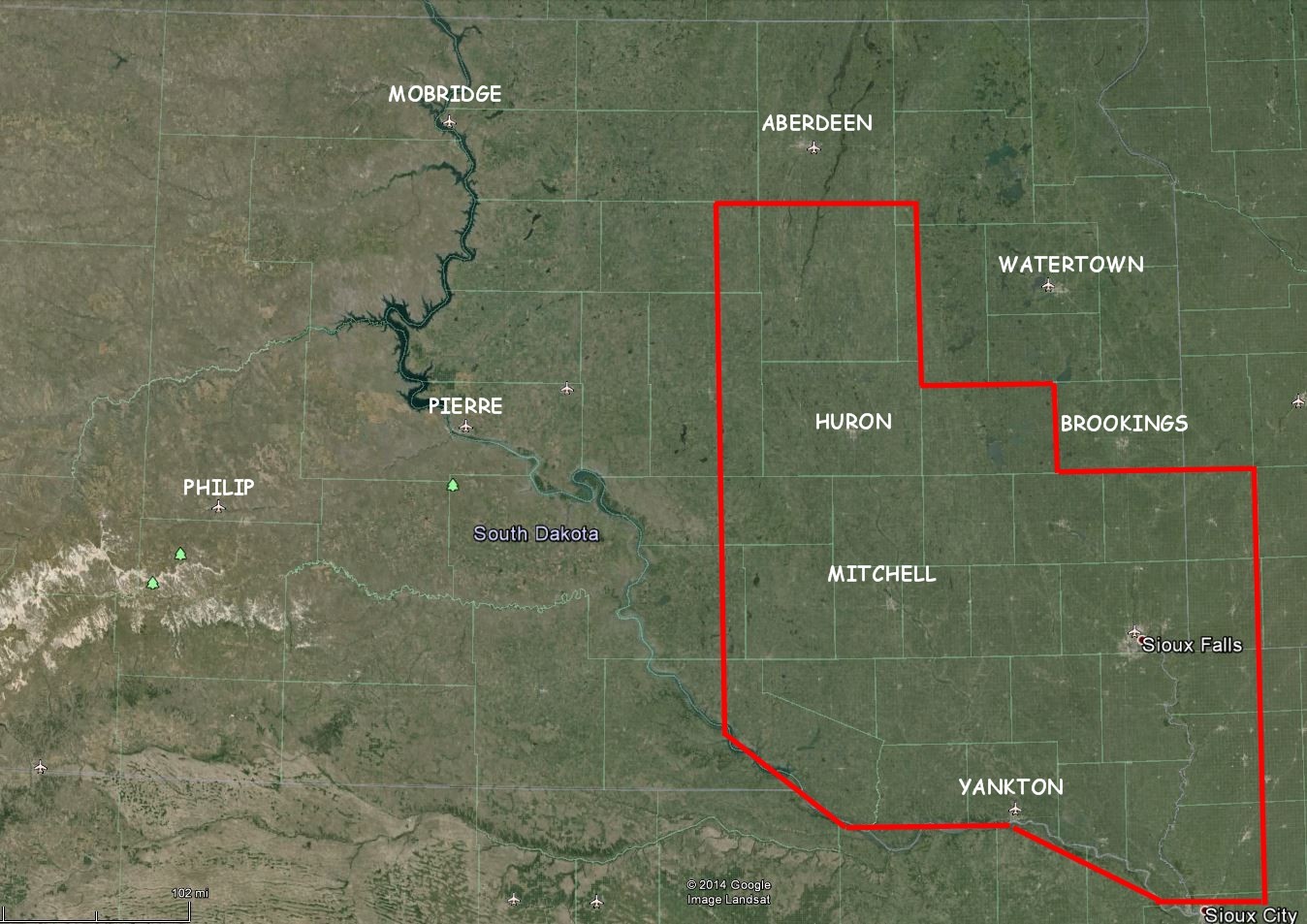

The Huron flight plan area was all of southeast South Dakota, a portion of southwestern Minnesota and a bit of extreme northwest Iowa. Most of our workload was generated from Sioux Falls but Huron, Mitchell and Yankton FSS’s were busy at times.

WEATHER ISSUES

Snowed In

The only time I was ever stranded at the airport was in Huron. South Dakota is known for harsh winters and everyone has their stories so this is one of mine.

I was scheduled to go to work at 0800 on a Saturday morning. The weather was pretty bad that morning and there was a blizzard warning so when I left home I knew full well that there was a chance I could be stuck once I got to the airport.

When I got to work there were four of us there – the midnight shift who was going home, the 0600 specialist, and the Flight Watch specialist who had come in at 0600. There were also four guys from the NWS, two who were coming on and two who were going off shift.

The airport manager came in and said that he was going to make one more trip out to the highway with the snow blower and then was going to quit plowing, so anyone who wanted to leave the airport had to go and anyone who stayed should plan on being there until the storm was over. Don and I were both EFAS rated, so one of us had to stay and since I’d brought extra food, anticipating the situation, I agreed to stay and Don insisted that he’d stay too. The guy coming off the mid and the other 0600 shift guy went home.

It was fairly busy because the largest/busiest airport in our flight plan area was Sioux Falls and since they were not being significantly affected by the storm, it was business as usual for them. About 11 PM we dug one of the cots out of the storeroom that were kept specifically for this type of situations. We set it up in the back room and I slept until around 0300 or so and then Don took his turn to get 3-4 hours of sleep.

The airport manager had been hanging out mostly in the terminal building through the storm and on Sunday he offered to make sandwiches in the airport restaurant and bring them over. He had to use the snow blower to cross the 100 yards or so of the ramp and deliver us the sandwiches.

By late afternoon the storm seemed to be abating but the winds were still very strong. I personally think it quit snowing a couple of hours before the weather observer recorded snow ending but it was blowing so bad that it was impossible to tell the difference between snow and blowing snow.

Finally, around 2100 the facility manager with the help of a friend in a big 4×4, managed to get out to the airport with a relief specialist, and then he gave us a ride home. Driving through town there were drifts at the intersections that were 20-25 feet high with just a single lane cut through for vehicle traffic. I found a drift across my driveway that was 9 or 10 feet high and it was Tuesday before I was able to get to the airport to get my car.

ACCIDENTS AND INCIDENTS

Deposition

My next-door neighbors in Huron were an elderly couple, Elmer and Stella, who were in their 90s. They had a son who was a railroad engineer and a pilot. I’d met him, by chance, when he flew into Jamestown several weeks before we moved to Huron – months before we ended up moving in next door to his parents.

Elmer and Stella had a grandson, Dan, who worked for the National Weather Service and in 1980 he and his family moved to Huron from Florida. Besides working in the same place – the NWS shared the building with the FSS – Dan had kids about the same age as our kids and when he’d come over to mow his grandparent’s lawn we’d generally have a beer and visit.

In August of 1982 Dan and his dad departed Huron headed to Oshkosh, WI to attend the annual EAA fly-in. I was working on the In-Flight position the morning they departed.

A short time after they departed, Mark, who was on the Broadcast position (adjacent to In-Flight), took a phone call and then asked me to see if I could contact Dan’s aircraft on the radio – there was a message for them. I called and when they responded I told them we had a message for them and handed the microphone to Mark. Mark told them that the airport manager thought their aircraft might have been struck by lightning during the early morning hours when a line of thunderstorms had moved across the airport. There was a chunk of concrete missing at a tie-down where their aircraft had been parked.

Dan’s dad responded, saying that they had just gotten through the line of storms and didn’t want to turn back. They would stop enroute and have the aircraft checked out. I learned much later that they did stop in Brookings, SD and no damage was found during the inspection.

Dan and his dad flew on to Oshkosh, spending the remainder of that day and all of the next there. That evening they flew to DeKalb, IL, picked up Dan’s sister and headed home to Huron. Sometime around midnight, over Iowa, they crashed and everyone was killed.

About 2 years later I was notified that I would have to give a deposition in the case. Dan’s widow was suing the FAA, Piper aircraft, and the FBO who rented the aircraft. I was being deposed simply because I’d called the aircraft so Mark could relay the message! In reality it was a fishing expedition and the lawyer was trying to find someone to pay up. After about four very intense hours with the lawyers I realized they weren’t interested in what I had done; they were just trying to find a loophole in our procedures that would result in the FAA being found at fault.

The FAA was released from the lawsuit a couple of weeks after my deposition. I never learned if anyone got any money out of it because Dan’s mother and grandparents hadn’t been part of the lawsuit and his widow had moved back to Florida.

Uneasy Night

I had worked an 0800-1600-day shift during which, for some reason, I never rotated away from the Pilot Briefing position. The next day I was scheduled to work 0600-1400 but took the day off to go to Sioux Falls for something but I then came back on shift at midnight. The specialist I relieved gave me a routine pre-duty briefing and departed.

After doing administrative duties, like traffic count, etc., I was straightening up the desks and noticed a Weather Service accident report. Looking at it I noted it was for a fatal accident that occurred the evening after my day shift and realized that the aircraft identification was one that I had been given for 3 or 4 of the weather briefings that I had done that day. The trouble was that I couldn’t remember any specifics of the briefings – about all I could recall was that they’d all been for different destinations.

When I went to check the briefing logs for the day I found that everything had been put into a locked file – standard procedure following an accident – so there was no way I could know if I had talked to the pilot and whether the briefing had in any way been contributing. It made for a long night as I wondered about my part in the event.

Finally, when the 0600-shift arrived I found out that I had indeed briefed the pilot and the conditions – scattered snow showers along the route with localized IFR conditions – were exactly what the pilot encountered and apparently what caused the accident. The tapes had confirmed that the pilot was given an accurate route forecast and decided to proceed anyway with tragic results.

Thanksgiving

I believe the saddest Thanksgiving I ever spent was while working at Huron.

It had been an unusually nice day with clear skies and relatively warm temperatures, but pilot briefing was difficult because a cold front was dropping south though North Dakota with low clouds, wind, snow and cold temperatures. We’d been watching the deteriorating conditions all day as they steadily moved south, but for some reason the forecasts for southern North Dakota and all of South Dakota continued to call for nice weather. Only after the weather deteriorated at an airport following frontal passage would we see an amended forecast reflecting what was coming. Consequently, we were giving briefings using the forecast material but warning pilots that we anticipated the forecasts were wrong – we called this “trending” and was, in my opinion, the reason Flight Service weather briefers were there.

In the late afternoon we got a call from the sheriff’s office letting us know that an aircraft had crashed near a small town about 40 miles northeast of Huron and asking if we had any overdue or missing aircraft – we didn’t – and after checking the logs, we found nothing that would likely have been in that area. When we asked for more information about the aircraft we were told that the weather wasn’t very good (the front had passed) and the wreckage was burning. Because it was fully engulfed and the fire was so hot, they couldn’t read the aircraft identification or even tell what color it had been.

Then we started getting phone calls.

The regional TV stations had gotten the story and put it on the air. We were swamped with calls from distraught people who had friends or family flying and were concerned that they might be the victims in the accident. In a few cases we were able to advise that we’d talked to the pilot or aircraft and allay their fear but in most cases, we weren’t able to tell them anything helpful.

Eventually we got a call from the scene and again they couldn’t tell us anything for certain about the aircraft except that it was a high wing, probably a Cessna, and there were 5 victims. They said it appeared to be 2 adults and 3 children but they weren’t even sure about that.

Finally, we got a call from a guy near Watertown who had loaned or rented his plane to a guy so he could fly his family to Mitchell for a Thanksgiving family gathering. He was concerned because the weather had gone bad and the plane wasn’t back yet. He said the family consisted of husband, wife and three kids under the age of ten. He hadn’t heard any of the news stories so wasn’t aware there had been an accident.

I don’t recall ever learning what the official probable cause was but have always thought that it was probably weather related because the crash site was about ten miles into the area of deteriorating weather. We discovered that the pilot had checked the weather with the Watertown FSS before departing early that morning. He’d been told that all forecasts indicated the weather through all of eastern South Dakota should be excellent VFR for the entire day. There was no indication that the pilot had rechecked weather before departing for the return flight on Thursday afternoon so he was probably caught by surprised when he encountered the low ceilings and snow.

PEOPLE AND THINGS

Who?

Each year Huron, SD hosts the South Dakota State Fair during the week prior to Labor Day, and in 1979 this was the last full week of August. I had reported to Huron from Jamestown, ND at the beginning of August and was working my first midnight shift alone during the middle of that week.

During the pre-duty shift briefing I was told that “Bill Janklow was sleeping in his plane on the ramp right outside the FSS door and if anyone needs to reach him he’d like us to wake him”. Of course, my response was something like “Who the heck is Bill Janklow”? And the answer was “He’s the governor of South Dakota”. Yeah, right… the governor is sleeping in an airplane. I figured this was some kind of initiation prank they pull on new guys. I was assured it was no joke. Janklow had flown his own plane over to the fair but the Pierre, SD weather had gone below minimums due to fog, and there were no hotel rooms to be found in Huron.

I didn’t realize a couple of things. First off – South Dakota is a small state and it’s amazing who you rub shoulders with. Secondly – Fred Janklow, Bill’s brother, had been a specialist at Huron FSS and so most of the specialists were somewhat acquainted with the Janklow family.

So anyway, I decided to operate on the premise that the governor might be out on the ramp, but if no one called it wouldn’t matter.

Someone called saying he was Janklow’s son and he was supposed to drive to Huron and pick his dad up, but only a few miles east of the Pierre it was crystal clear. He wondered if it might clear off so Bill would fly home and they’d have driven over for nothing. The forecast supported the clearing trend so they decided to go home.

Now I believed that the governor was sleeping in his plane, but I’m counting on the weather improving at Pierre. If it didn’t improve I’m going to have to explain why I agreed with a teenage kid who didn’t want to drive 200 miles at 3am.

It all worked out. The Pierre weather cleared off and about 0500 the governor came in, used the restroom, checked weather, filed a flight plan and headed home.

So, that’s how I met the governor.

Conflict

The early 80’s saw a lot of changes in Flight Service as the first hints of consolidation started to appear. One of the early changes was direct phone lines installed at some airports and they could blur some of the established facility boundaries. One such case was a phone line in Mobridge, SD that rang into Huron FSS, even though Mobridge was in the Pierre FSS flight plan area. This really annoyed Pierre FSS personnel and consequently any time we got a flight plan cancellation at Mobridge we followed prescribed procedures exactly and forwarded the information to Pierre.

On one occasion I was on duty as CIC (Controller In Charge) when the facility manager and both supervisors were gone somewhere. We forwarded a flight plan cancellation for an arrival in Mobridge and moments later I received an interphone call from Pierre. The caller was the facility manager calling to complain about us “stealing” their traffic. I told him I believed we had handled the situation correctly and that he had no reason to complain. A few minutes later the admin line at the supervisor’s desk rang and when I answered it was the manager from Pierre. We had essentially the same conversation. Then a few minutes later the secretary came out of the office to say that the manager from Pierre was calling for our manager and did I want to talk to him. So, for the third time I went through what we did and how it was procedurally correct and he was welcome to call again the next day if he wanted to talk to our manager.

He did call the next day and whatever the conversation was it ended the problem. The people in Pierre were still not happy, but we never had any further complaints. Ironically, I would replace this manager in Pierre when he retired 6 or 7 years later.

Pilots and owners

There was a guy in Huron who owned a C310 but wasn’t a pilot. We never talked to him – I’m not sure he ever visited the Flight Service. Nearly every day he would work on the aircraft and two or three times a week he would pull it out of his hanger and start it up and run it a while and then push it back in the hanger. It never flew. Never did figure that out.

Another character was a lawyer who retired in his 70s and decided to fulfill a lifelong dream. He bought a Piper Cherokee and got his pilot license. He was a very nice guy but always a bit of a concern as a pilot. Often times we would see him in his leather jacket and white silk scarf taxi over to the terminal building to go in to have coffee. One day he came into the facility and said he was going to see how high he could get his plane. After takeoff he called overhead at 3,000 feet (field elevation was 1290). Then he reported 4,000 feet sounding pretty calm. Then he reported 5,000 feet sounding a little excited. Then when he reported 6’000 feet with a tremor in his voice and said, “That’s high enough, I’m coming down”

There was a doctor in Mitchell, SD who flew frequently. Apparently, he had another practice (or some kind of business) in northwestern Nebraska. I understood that he had been an instrument rated pilot but that ticket had been pulled and he was strictly VFR during the times I dealt with him.

One day he departed Mitchell and when we asked for a pilot report on cloud bases he gave us bases and tops of the overcast layer!

He would often call ahead when returning to Mitchell and ask us to relay messages. On one occasion he asked us to call the hospital and advise them of his ETA. When I called the hospital, his nurse told me that if this call is about Mrs. So-and-So he shouldn’t worry because she’d already had her baby. I passed this info and his response was, “How’d she do that?”

The final straw for our message relaying service was the afternoon when he asked us to call his home, give his wife the ETA and tell her they were going out to eat at a steakhouse. His wife asked us to tell him they were going out to have pizza. When we told him that he said we should call her back and tell her it was steak night not pizza night. We never relayed messages after that unless they were medically related.

We had a pilot who flew in regularly. I don’t know anything about him except that he seemed to be a competent pilot and he stuttered. When he would call in for an advisory it was agonizing because we knew who he was, and generally what he was trying to say long before he could get the words out. We always wanted to finish his sentences for him just to clear the air.

One day, on Flight Watch, I received a call from an aircraft with a pilot report. When I asked for his position I couldn’t understand what he was saying. After three tries I finally asked him if he could give me the identifier for the location and he responded with H – O – N. He was over HURON! To this day I can’t imagine how he was pronouncing it in such a way that I couldn’t understand him!