ANDERSON INFIRMARY

1421 TWENTIETH AVENUE

MERIDIAN, MISS.

November 30. 1931

Mrs. F. J. Jennings

509 Third Street S. E.,

Washington, D. C.

My dear Mrs. Jennings:

We have meant to write you before now, but for one thing it was a very hard task, and then we have been so very busy.

It was such a sorrow for us to have to give up Mr. Jennings. The doctors and nurses did everything possible for him, and he put up such a game fight from the very beginning, but it seems it just had to be. He made a lasting impression upon us all. He had a dynamic personality, which we all felt the moment Dr. Fowler brought him in. He was brought in by a Doctor Fowler, who lives out from Meridian, about two-thirty P. M. Wednesday, November 11th. Dr. Anderson insisted that he be operated on that afternoon, but he would not consent, as he said he had just about another week’s work to complete and then he was getting a leave of absence to be with you. Doctor Anderson was so worried over him, however, that he had the Laboratory Technician make another blood count that night about ten o’clock, after which he was told that he was taking his life in his hands if he did not have the operation. He then consented and was operated on around twelve o’clock, when it was found that periotinitis had set in. We felt that with his wonderful constitution he might be able to combat it. I want to explain to you also the reason we did not telegraph you immediately. Your husband would not consent to have you disturbed. All during his ill-ness his every thought was to save you worry. We begged him all along to let us communicate with you and when he kept refusing, we got in touch with Mr. Thomason in Birmingham and had then wire you. We felt that you should know and know at once that his condition was serious. We were so sorry you could not come to him, but we were so glad his sister got here in time. When we knew she was coming, we all prayed that he might live to see her and know her. And he did. Of course he was so sick that he could not talk to her very much, but still it must have meant such a lot to him to have his sister come to him. We all fell in love with Mrs. Glennon. We never felt that she was a Stranger. It was so hard on her to have all the responsibility of looking after everything alone. We helped her all we could, however, and I feel that we did a little toward making her burden a little less hard.

I am Dr. Andersen’s sister. I help him in different ways around the hospital, – – office, kitchen, and in fact a little of everything. I spent nearly seven years in Washington during the war and after, and am so familiar with the neighborhood in which you live. During practically the whole time I lived at 206 A Street Southeast and took my meals on Third Street S.E. I went in and told Mr. Jennings that I wanted to talk Washington with him and he smiled and said he’d love to and asked me too come in and stay with him. He was not able to be disturbed and so of course I did not talk to him. You’ll never know how grieved we were for him to go. If he had not been so lovely in his manner and such a cheerful person in his deepest sufferings, perhaps we would not have felt it so keenly. I want you to feel that everything in the world was done for him that was possible. My brother worked with him with all hi a power. He came over about eleven o’clock the last night he lived and spent the whole night. Your husband wanted him. He loved to have “Doc”, as he called him sit by him and talk to him, holding his hand. Dr. Anderson, as Mrs. Glennon will tell you, is a very lovable person. To know him is to love him. During the six days your husband was here, he learned, to love him. Many times Dr. Anderson came to him just to comfort him. We called in two other very fine Doctors to consult with and they agreed that everything possible was being done.

I wish there was something that I could say to you to make your grief less hard; but there isn’t. I want to make you feel that every one was kind to him. He said we treated him as though he were a relative. He had lots of flowers given him by different ones. It is so hard for our loved ones to be alone in their last illness, but I want you to know that, although we know that nothing could take the place of his family with Mr. Jennings, we did all we could to cheer him up. I want you all to know that. It may be that I shall go to Washington next summer and if I do, I, shall look you up. I want very much to see you and the three babies. I have a little son seven years old, an adorable little fellow.

I have not meant to write such a long letter, but it has lengthened out in spite of me. I know that your burden is heavy and I am hoping your new baby has come by now to help make your heart a little happy.

I am enclosing, herewith, an itemized bill, as I am sure you want to get all those details off your mind as soon as possible.

In closing let me ask you to accept the heartfelt sympathy of us all way down in Mississippi. We have all thought of you so much, – you and your babies.

Very sincerely,

Claudia A. Estopinal

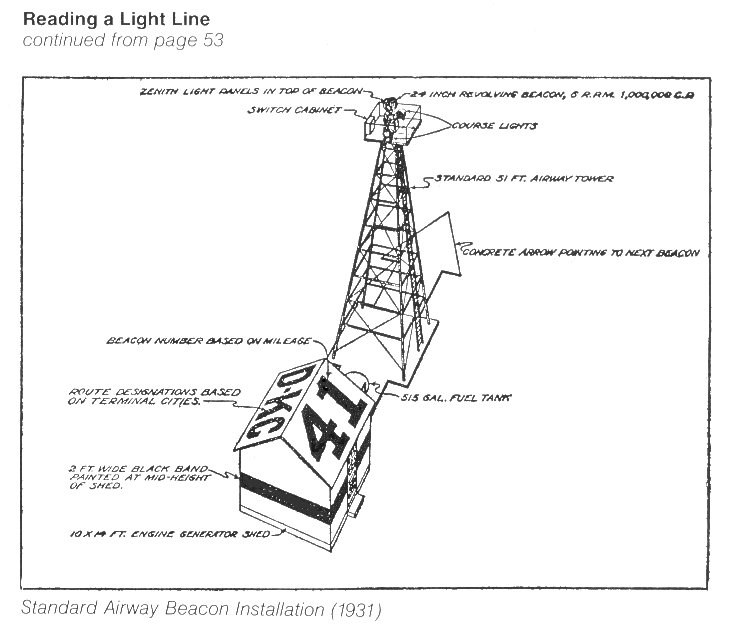

Light Line Tower

Light Line Tower Nome FSS building, Alaska, 2006

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 2006 Nome FSS building, Alaska, 2006 (center of photo)

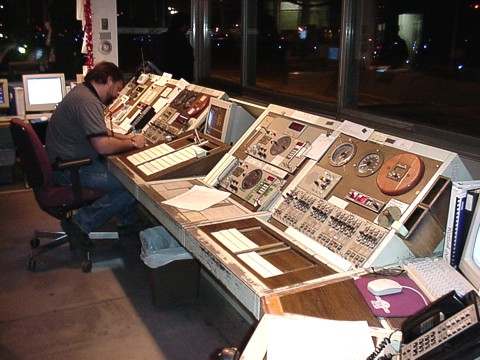

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 2006 (center of photo) Nome FSS, Alaska, radio frequencies and wind instruments panel, 2000

Nome FSS, Alaska, radio frequencies and wind instruments panel, 2000 Nome FSS Inflight position Alaska, 2000

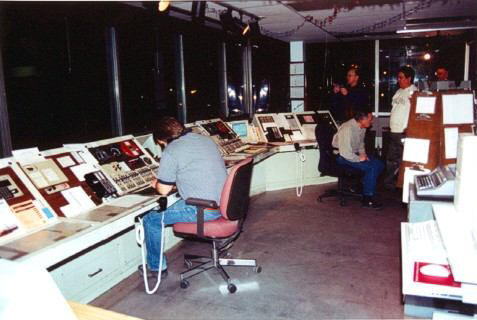

Nome FSS Inflight position Alaska, 2000 Nome FSS operations area, Alaska, 2000

Nome FSS operations area, Alaska, 2000 Nome FSS directional finders, Alaska, 1999

Nome FSS directional finders, Alaska, 1999 Nome FSS Inflight positions, Alaska, 1999 (specialist name unknown)

Nome FSS Inflight positions, Alaska, 1999 (specialist name unknown) Nome FSS Inflight positions, Alaska, 1999 (specialist name unknown)

Nome FSS Inflight positions, Alaska, 1999 (specialist name unknown) Nome FSS Inflight positions, Alaska, 1999 (names unknown)

Nome FSS Inflight positions, Alaska, 1999 (names unknown) Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998 Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998 Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998 Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998 Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS building, Alaska, 1998 Nome FSS equipment room, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS equipment room, Alaska, 1998 Nome FSS equipment room, Alaska, 1998

Nome FSS equipment room, Alaska, 1998