History written by John Schamel.

This page contains a brief history about the development of air traffic data communications.

One thing man developed early was written communications. The ability to write down information so it could be used later was a milestone in civilization. The next logical step was an efficient means of communicating this information to someone else someplace else.

The Model 28 ASR (Automatic Send-Receive). Note the keyboard on right. The small window to the left of the keyboard shows the baudot tape. To the left of the window – the flat silver area – is the Transmission Distributor (TD)

The developing air traffic service of this century was no different. Communicating information through a nationwide system had to be accomplished in order to help aviation grow.

The early Air Mail Radio Stations (AMRS) of the 1920s used radio telegraphy to communicate with each other. The information was written by the radio operator as they translated the dots and dashes back into English. So Air Traffic’s first ‘data communications’ system was a pencil and paper and the radio. Messages on weather, aircraft positions, airfield conditions, and other information would be passed up and down the airways in this manner.

Weather information, the pilot’s main concern, was often sketchy. In the 1920s the Weather Bureau was part of the Department of Agriculture. Weather Bureau offices were located downtown in the business and government districts. Weather observations were taken there, and not at the airfield. Although the Weather Bureau was part of an extensive teletype network for collection and dissemination of weather information, the early air traffic system was not a part of their network. AMRS personnel and the pilots themselves used telephones, when available, to obtain weather information. The pencil remained an important part of the data communications system.

The Air Commerce Act of 1926 changed this situation. The Weather Bureau was tasked with provided more and better weather information to pilots. During the 1930s, as municipalities developed airports, Weather Bureau offices gradually migrated from the downtown areas to the airports.

Despite having the Weather Bureau at the airport, its teletype system remained for their sole use. Air Traffic still used the pencil in conjunction with telephones and radio telegraphy to pass information up and down the airways.

A close up of the Tape Perforator mechanism with baudot tape.

Teletype was first introduced to Air Traffic in 1928. By 1933, the national system was complete. Information on weather, aircraft positions, and airport conditions could be sent directly to any station. Many of the codes developed during the radio telegraphy days were carried over to teletype. Q Codes, as they were called, were a Morse code shorthand developed to make it easier for the radio operators to communicate. Many Q codes still exist today and are still used throughout the world.

Originally started with only one circuit dedicated to air traffic use, the system rapidly reached saturation. Another circuit was added. The alphabet was used to name the circuits. Circuit A handled only weather and NOTAM (Notices to Airmen) information. Circuit B was used for flight plans, flight notification messages, and other administrative messages. These circuits were later called services, and remain with us today as Service A and Service B.

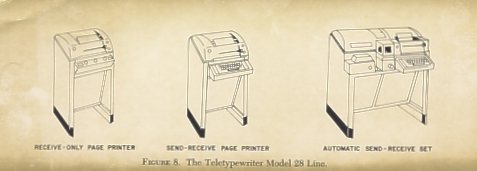

The Teletypewriter Model 28 line of equipment

Teletype was a mechanical marvel of its day, a forerunner of the computer networks that span the globe today. Imagine a vast network of equipment that had the ability to transmit and receive messages over long distances in a matter of minutes. Larger stations had equipment that could receive different messages at the same time!

An air traffic specialist would type out a message – be it a weather report, a pilot report, or an aircraft position report – on a small, customized 31 key keyboard. As the specialist typed, the Model 28 ASR (Automatic Send Receive) would perforate a small tape, similar to Wall Street’s famous “ticker tape”, called baudot tape. The tape would contain all the proper addressing, priority coding and end-of-message codes in addition to the message text. The specialist would then take the perforated tape and load it into a Transmission Distributor (TD). The TD unit would feed the tape and read the perforations. The perforations would be turned into electric impulses that would be transmitted to the addressed destination.

A classroom poster used at the Air Traffic Academy. The arrows on the second row of keys and the symbols on the third row were used for encoding weather observations. The symbols were phased out with the introduction of LSAS – it could only use alphanumeric characters.

At the destination, the electric impulses would go into a Model 28 Printer. The message would be typed out onto a roll of yellow paper.

The teletype system, with few modifications, served the Air Traffic Service well for many years. Teletype served in Flight Service Stations into the late 1980s. Stations still using teletype received equipment from other stations that were being upgraded to use as spare parts. Equipment manufactured and purchased in the 1930s performed government service for almost fifty years. In contrast, the ‘oldest’ computer system in use with the Air Traffic Service has only seen slightly more than thirty years. Learn more about the teletype and fonts. Learn more about the teletype and fonts

The teletype lab at the FAA Air Traffic Academy where Flight Service specialists learned the basics of teletype. Teletype instruction finally ended in October 1985.

The introduction of radar in the en route centers in the late 1950s and early 1960s opened the door to computerization. The computers were first used to run the radars. Terminal radar systems, starting in the early and mid 1960s, followed the same pattern. Flight Service remained with the teletype system for handling weather and flight plan information.

The forerunners to ‘main frames’. An example of the Automatic Data Interchange System, which exchanged large amounts of teletype messages between stations in a minimum amount of time.

Growth in air traffic and strides in computer technology called for a better way of doing business. With the air traffic system reaching saturation on an almost daily basis in 1968 and 1969, it was obvious that teletype was not a long range option. It was estimated in 1969 that to expand the current Flight Service system to meet projected 1983 traffic loads would cost $250 million dollars a year. An initial investment of $60 million for automation would significantly reduce that cost. Part of the “National Aviation System Ten Year Plan” unveiled in February 1970 called for $56 million for the reconfiguration and improvement of the Flight Service system.

Another means of data communications within an airport. The telewriter allowed a weather observer to use a special pen and write the observation on a special pad. This handwritten message would then be printed at other locations around the airport, such as the control tower, flight service station, or airline operations office.

The long-range problem was addressed, but what about the short range? The aging teletype system wouldn’t last until the new systems came on line in the late 1970s. A short-term solution was found – blend teletype with computers.

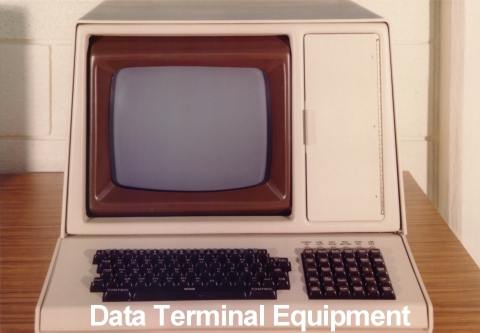

Western Union – the company that made teletype famous – built a computer based data communication system for the FAA. Called Leased Service A System – LSAS – it replaced the paper and baudot tape with CRT screens and regular keyboards. It dealt only with the Service A functions of weather and NOTAM information. Controllers could request weather and NOTAM information by typing commands on the keyboard. The reply would be displayed on the screen. A printer was part of the system so controllers could print out seldom changing reports, such as Area Forecasts and Winds Aloft Forecasts.

The position equipment of LSAS and later LABS

Running the facility system and linking it into the national system was a computer console called a GS 200. The LSAS was lightning fast compared to the slow mechanical circuits of teletype. Weather reports and forecasts were available in a matter of minutes compared to the slower transmission of grouped reports – called polls – that came over the teletype. Flight plans and other traffic related messages remained on teletype, though.

The GS 200, the unit that linked the Flight Service Station to the national Service A and B systems. This unit allowed the supervisor to reconfigure or restart the facility as required.

Running the facility system and linking it into the national system was a computer console called a GS 200. The LSAS was lightning fast compared to the slow mechanical circuits of teletype. Weather reports and forecasts were available in a matter of minutes compared to the slower transmission of grouped reports – called polls – that came over the teletype. Flight plans and other traffic related messages remained on teletype, though.

Later the system was upgraded to include traffic messages on Service B. The blended system, called Leased A and B Service – LABS, finally retired the teletype equipment from air traffic. Flight plans and movement messages could be typed directly on to a CRT screen at a dedicated Service B position and transmitted from the same screen. Incoming messages printed automatically on a dedicated printer. Weather briefers, though, still used the paper forms as they copied flight plans from pilots. The completed form would be passed to the person on the Service B position. LABS had eliminated some, but not all of the paper used in Flight Service.

Western Union equipment at the FAA Air Traffic Academy. This position is for LSAS, used for pilot weather briefing training. The unit on top is a closed circuit TV set for viewing weather charts.

Part of the 1970 plan called for consolidation in addition to modernization of Flight Service. A final number of 61 was fixed for Automated Flight Service Stations (AFSS) to replace the almost 400 flight service stations then in existence. Modernization through computers would allow controllers to provide more and better services at a fraction of the cost.

McAlester, Oklahoma AFSS

The Modernization Plan called for three separate ‘models’ to be phased in during the consolidation process. Model One was the first to combine Service A and B at the same position. Flight Services controllers could now provide weather information and file flight plans from the same position, all without paper. The computer could link the two functions together, providing a customized display of weather information tailored to the route on the stored flight plan. The first Model One facility – Bridgeport Automated Flight Service Station – opened its doors on March 3, 1984. The ‘paperless era’ of air traffic had finally begun in Flight Service.

Fairbanks, Alaska operations floor

The Flight Service Consolidation and Modernization Program was finally completed on September 30, 1997, when the last two Flight Service Stations (FSS) were closed.

Changing costs and technologies modified the original FSS Consolidation and Modernization Plan. The Model One system was upgraded and renamed Model 1 Full Capacity (M1FC). It incorporated many suggestions from the controllers who used the Model One system.

A typical Model One position in an AFSS

The explosion of computer technology in the mid and late 1980s opened up new and better ways of doing business by computer. The next generation of data communications was proposed using ‘off the shelf’ equipment instead of expensive custom designed systems. Called OASIS, for Operational and Supportability Implementation System, it is scheduled for deployment to Flight Service in 2000.

Future OASIS console to be installed in all AFSS facilities

Flight Service controllers maintain their heritage daily at the Automated Flight Service Stations across the country. At each computer position some paper and a pencil is maintained for those who still do some business “the old fashioned way.”

Above article written by John Schamel

About the author …

John joined the FAA in 1984 and has been an Academy instructor since 1991. He taught primarily in the Flight Service Initial Qualification and En Route Flight Advisory Service programs. He has also taught in the International and the Air Traffic Basics training programs at the FAA Academy.

History has been an interest and hobby since childhood, when he lived near many Revolutionary War and Great Rebellion battlefields and sites. His hobby became a part time job for a while as a wing historian for the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

John’s first major historical project for the FAA was to help mark the 75th Anniversary of Flight Service in 1995.